Even more unexpected that Yoji Yamada’s turn to jidai-geki was Kore’eda’s sudden interest in not just the jidai-geki but the Chusingura story in particular. Along the way, he has discovered community and comedy and even a bit of romance, which had not been much of a factor in his earlier films (or later movies that I have seen).

Even more unexpected that Yoji Yamada’s turn to jidai-geki was Kore’eda’s sudden interest in not just the jidai-geki but the Chusingura story in particular. Along the way, he has discovered community and comedy and even a bit of romance, which had not been much of a factor in his earlier films (or later movies that I have seen).

He approaches the Chusingura story sideways. Soza is in Edo for a completely different revenge, out to avenge his father’s death over a silly squabble at a Go game. Soza, however, is a samurai skilled in only the ways of his father’s dojo, which is not much help in a real fight, as is quickly demonstrated by the chancer Sode who humiliates him despite being unarmed, eventually throwing him into the communal outhouse.

Soza has ended up in a tenement slum because it turns out his wife hasn’t been sending him the stipend the clan had provided for his revenge. There we meet a crowded cast, too crowded to remember all the names but each distinct in their characters – the ronin Hirano always in search of a job and never finding it and who every spring tries to commit harakiri and fails; the man who always wants to take the day off but his wife and daughter won’t let him, the landlord who is about to throw everyone out and his wife that has been bought from a brothel; the old scribe who also writes a revenge play for the cherry blossom festival; the peddlers who barely make ends meet; the old man who thinks he is dying who suddenly decides to live again when he meets a widow with diarrhea outside the outhouse; the village idiot Mago who collects the excrement and bounces when he is excited; the man who offers advice on anything, to name only a few.

He also meets the widow Osae and her son Shinbo, each of whom is pretending to the other that the father will return. Love blossoms though with each careful to not say anything about their feelings. Soza has started a school to teach the neighborhood kids (and some adults) to write. He eventually crosses paths with Kichiemon, a peddler who is one of the 47 Ronin, several of whom are holed up in a nearby hovel. They are suspicious of him and assign Kichiemon to keep an eye on him, and the two become friends over games of Go.

But still there is the question of his adauchi, made more difficult because he has met the man, now a laborer in the boats with a wife and a stepson of about the same age as Shinbo. When they meet through the boys, he finds he quite likes him, someone who has taken to his new life without regret. So he must struggle with a revenge against a man he both likes and which he is almost certain to lose.

Kichiemon has been the enigma of the Chusingura story. Only 46 men actually carried out the raid, without Kichiemon who had joined the group but was not a samurai by birth. Various motives have been assigned to his absence, but Kore’eda settles on a reason that will also provide Soza’s solution, a desire to pass on to his son more than just a a legacy of hate and killing. His solution to charges of cowardice is to pretend that he was ordered to spread the news throughout the land, a suggestion of one of the women.

Kichiemon has been the enigma of the Chusingura story. Only 46 men actually carried out the raid, without Kichiemon who had joined the group but was not a samurai by birth. Various motives have been assigned to his absence, but Kore’eda settles on a reason that will also provide Soza’s solution, a desire to pass on to his son more than just a a legacy of hate and killing. His solution to charges of cowardice is to pretend that he was ordered to spread the news throughout the land, a suggestion of one of the women.

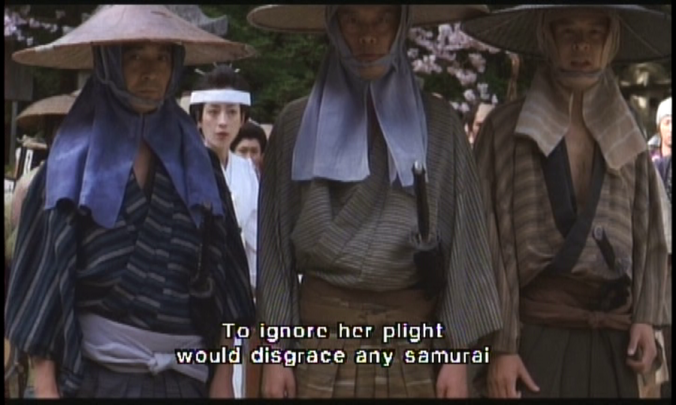

Soza’s solution to his predicament lies in a similar pretense. The adauchi play had been a failure when Mago had missed his cue and three passing samurai had mistaken the play for reality and offered to aid the widow and her son, causing Soza to flee in total panic.  It is revived again with Mago as the victim and all the residents convincing the local official that it is real, with even some guts spilling out to prove it and make the official decide not to look too closely.

It is revived again with Mago as the victim and all the residents convincing the local official that it is real, with even some guts spilling out to prove it and make the official decide not to look too closely.

In general the samurai don’t come out of it well, because they can’t distinguish between reality and their own little world. Not only can’t they tell the difference between a play and the real thing, they are utterly clueless about basic things like how to repair a sandal. The samurai who summons Soza back to the clan for a report on his lack of progress thinks the reason is because of the widow and her son, though Shinbo is eight and Soza has only been gone three years – as he says, “Kids grow so fast nowadays.” And of course the Chusingura clan are pursuing a meaningless death, and killing an old man in his sleep to boot.

The title comes from the poem written by Lord Asano before his death, but Mago provides an unusual gloss on the poem’s meaning when he comments that perhaps the cherry blossoms fall so easily because they know there will be another Spring. That attitude is ultimately adopted by Soza himself.

Excellent performances come from just about everyone. Junichi Okada never betrays his boy band background, Rie Miazawa as the widow adds to her long string of excellent portrayals, and Susume Terajima, one of Kore’eda’s most common players, is outstanding as Kichiemon. Only Tadanobu Asano seems wasted, not because of his characterization but because he has so little to do as the man Soza is pursuing.

In its setting among the very bottom of the social scale, it resembles Imamura’s Eijaneika, and with its theme of adauchi recalls Okamoto’s comedic Vengeance is a Great Business, without echoing either. Despite the centrality of the outhouse, it is never really vulgar.  It doesn’t try to paint the down-and-outs as more noble than they are, but it does buy into the long Japanese tradition of the community as a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. It is one of the most richly comic and humane of any of the samurai movies, able to deal both with its serious themes and with its comedy without belittling anyone, except perhaps the samurai themselves. It was a box-office disaster in Japan, for reasons that completely elude me.

It doesn’t try to paint the down-and-outs as more noble than they are, but it does buy into the long Japanese tradition of the community as a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. It is one of the most richly comic and humane of any of the samurai movies, able to deal both with its serious themes and with its comedy without belittling anyone, except perhaps the samurai themselves. It was a box-office disaster in Japan, for reasons that completely elude me.