Iguchi is nicknamed “Twilight” by the samurai he works with because he always goes home at twilight rather than stopping for a drink or two with his compatriots, but Twilight Samurai also takes place in the 1860s, the twilight of the samurai era itself when the Shogunate is about to fall.

Iguchi is nicknamed “Twilight” by the samurai he works with because he always goes home at twilight rather than stopping for a drink or two with his compatriots, but Twilight Samurai also takes place in the 1860s, the twilight of the samurai era itself when the Shogunate is about to fall.

Iguchi has good reasons to skip the drinking parties; he had a sick wife who only recently died, leaving him in debt for her medical bills and her funeral, and still needs to take care of two daughters of ten and five and a senile mother who rarely even recognizes him. His tiny stipend can barely support them, even when augmented by the sale of insect cages they make in the evening. And he loves his daughters, treasuring every moment he can have with them.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the return of the samurai movie genre around 2000 was its sudden interest for Yoji Yamada, who in his many earlier movies had almost exclusively dealt with contemporary life.* Twilight Samurai would begin a remarkable trilogy about samurai life adapted by Yamada with his long-time collaborator Yoshitaka Asama and all based on stories by Shuhei Fujisawa, which I hope to deal with in later posts. Though Twilight Samurai gives us two remarkable sword duels, Yamada’s primary interest had always been the family as it faced a changing modern Japan, so the story of Iguchi in particular can be seen as yet another of Yamada’s clear-eyed yet deeply sympathetic portrayals of people caught in a changing world over which they have no real control.

The movie is set in the northeast, so Iguchi’s situation is similar to that of Yoshimura in When the Last Sword is Drawn, but here given different clan names. We regularly see the bodies of peasants who have died of starvation floating down the river, and Iguchi’s girls often see the bottom of the rice bowl. Nevertheless, when a friend offers Iguchi a chance to go to Kyoto to earn money as the coming civil war simmers, he declines so he can stay with his family. Like many others, he senses that the old world is about to come to an end but says that if the samurai disappear he would be content to become a farmer.

Nevertheless, Iguchi has a problem beyond his debts. His mother is too old and senile and his daughters too young to take up the slack around the house after his wife becomes ill. After she dies, he can’t even afford the public bath or keep his clothes in good repair and is known by his smell, which even the Lord comments on during a surprise visit to the storehouse where he keeps records. It seems obvious to everyone that he needs a new wife (after all, what’s love got to do with it?). His officious uncle (Tetsuro Tanba in one of his last significant roles) orders him to marry a peasant girl he has selected, but Iguchi declines not because she is not samurai but because it would be an insult to the girl herself to be ordered into a marriage she doesn’t want. His friend Inuki has a sister Tomoe, for whom he has recently arranged a divorce after her husband turned out to be a drunk and a wife-beater. But when Inuki suggests Iguchi marry Tomoe, who loves him, the offer is refused because experience with his previous wife has taught him that a daughter of a richer family might start the marriage in loving happiness but will soon come to resent his lowly status and poverty. Nevertheless, Tomoe begins showing up a couple of days a week to help the girls and to clean house.

The ex-husband demands Tomoe return and challenges Inuki to a duel, but Iguchi volunteers to fight in his place. He shows up with a wooden club and in a fight that shows off Hiroyuki Sanada’s atheticism, the husband is knocked unconscious. This will, however, come back to haunt Iguchi, for when the Lord dies, the clan splits into factions over an heir, and because Iguchi has demonstrated his skill with the short sword, he is ordered to kill the last holdout boarded up inside his house.

He shows up with a wooden club and in a fight that shows off Hiroyuki Sanada’s atheticism, the husband is knocked unconscious. This will, however, come back to haunt Iguchi, for when the Lord dies, the clan splits into factions over an heir, and because Iguchi has demonstrated his skill with the short sword, he is ordered to kill the last holdout boarded up inside his house.

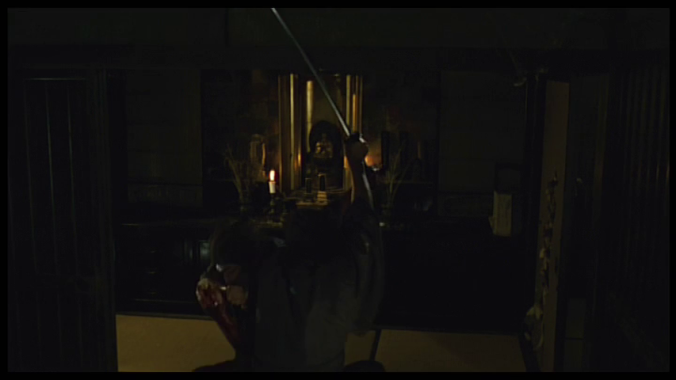

This leads to a remarkable scene that is really the dramatic core of the movie. Iguchi is in a way on a suicide mission, for Zenemon the holdout is a superb swordsman who has already killed the clan’s best, leading many others of higher rank to decline the job.

He is also desperately isolated, slowly going mad in the darkness, in a stunning characterization by Min Tanaka in his first movie after decades as an avant-garde dancer. He hopes to escape over the mountain and Iguchi wants to let him do so after putting up a show for the clansmen outside, but when Zenemon realizes that Iguchi is only carrying a short sword (which can be carried by commoners and will in later years become the primary yakuza weapon) samurai pride gets the better of him. This leads to a murky running battle indoors until at last, in a powerful symbol, the long sword becomes Zenemon’s downfall.**

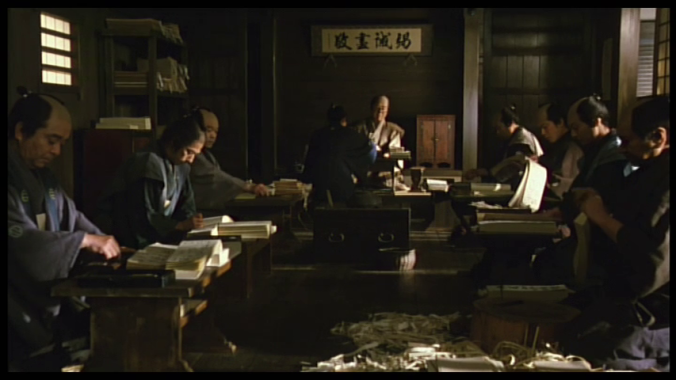

I had always assumed the salaryman culture grew out of the rise of the merchant class, but here Iguchi is in effect a salaryman in kimono.*** He tries to survive on his fixed salary, sitting all day in an office keeping records in a job he will hold for life, and when the day is done the others go drinking with the boss, just like the modern salaryman, often seeing wives and family for only brief moments before the next morning.  The twentieth century salaryman life was ostensibly more open to commoners than were the 19th century samurai, but it always required a university degree, making it an equally exclusive world once a young man gained admittance. The office hierarchy, the college degrees essentially dependent on wealth (usually inherited) to pay the tuition, the difficulty of promotion to a better pay level without family contacts, the company leadership passed down to the boss’s son or the husband of the boss’s daughter, and the layers of authority mirror the traditional samurai clan organization of the Tokugawa era (just as the yakuza gang, at least in movies, resembles the samurai world during the Warring Clans era, often resorting to violence in a search for territory or leadership).

The twentieth century salaryman life was ostensibly more open to commoners than were the 19th century samurai, but it always required a university degree, making it an equally exclusive world once a young man gained admittance. The office hierarchy, the college degrees essentially dependent on wealth (usually inherited) to pay the tuition, the difficulty of promotion to a better pay level without family contacts, the company leadership passed down to the boss’s son or the husband of the boss’s daughter, and the layers of authority mirror the traditional samurai clan organization of the Tokugawa era (just as the yakuza gang, at least in movies, resembles the samurai world during the Warring Clans era, often resorting to violence in a search for territory or leadership).

Interestingly, Yamada continues the old Japanese dramatic tradition that the most important conversations must be conducted by characters not facing each other. Whether declining his friend’s offer of his sister, declining her own offer to live with him, or telling her he has changed his mind only to learn she has accepted another offer, Iguchi does not face the person he is talking to.

Nor does Zenemon even look at Iguchi while describing his past life in another clan and the loss of his wife and daughter while wandering as a ronin before finding his sword-teaching position here. As Japan had neared the millennium, that practice had been slowly fading from modern-dress movies in which people more directly speak to each other.

Leaving such observations aside, Twilight Samurai is a superb movie, directed with Yamada’s usual invisible technique, almost as if Naruse had made a samurai film. He elicits complex and detailed performances from the entire cast and provides a murky, confined fight that would have made even Misumi proud. My one personal quibble is that it is narrated by the now grown up 5-year-old daughter, who could not have seen or understood many of the scenes we are shown, and which leads to an unnecessary epilogue that walks up to the edge of sentimentality that had previously been avoided despite the many family scenes. However, the daughter’s narration makes it easy for a Euro/American viewer to follow aspects of the story that might be otherwise confusing and perhaps indicates that for even Japanese audiences of the 21st century, many of the things left unsaid in fifties and sixties period movies now needed to be said.

* As far as I can determine from his credits, Yamada’s only previous “period” film was Final Take, set inside Shochiku studios in the thirties.

** We have seen a similar combat and conclusion in Hunter in the Dark, though in that film the short sword is used against many long swords and without the symbolic power seen here.

*** Another scene underlines this similarity. In one of my earliest posts, I had commented on the strange practice of the salaryman husband simply shrugging his coat off onto the floor rather than hanging it up himself or handing it to his wife before it hit the ground. As Iguchi prepares for his fight, he must put on his one good kimono; to do this, he shrugs off the work kimono onto the floor while Tomoe stands behind him like one of Ozu’s wives, holding the new kimono for him to slip his arms into before she picks up his other kimono from the floor.

Pingback: Hidden Blade / Kakushi ken: Oni no tsume (2004) | Japanonfilm

Yamada is a very strong director but a really terrific screenwriter. (Your offhand comment that it is almost as if Naruse had made a samurai movie is spot-on.) In his DVD commentary, Yamada criticized Kurosawa’s samurai films, pointing out that none of his samurai heroes is ever even wounded by his opponent, which is just not realistic. This criticism strikes me as valid. (It’s as if to Kurosawa, being wounded even slightly would spell dishonor.)

However, I think that Yamada perhaps goes to the other extreme here, having the adversaries hacking away at each other. It can be reasonably assumed that a samurai would have a basic understanding of human anatomy and thus know what parts of his opponent’s body would be most vulnerable to attack. However, in this case, the men are fighting in a darkened house, so Yamada’s approach does make a certain sense in context.

LikeLike

Pingback: Oriume (2002) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Hana / Hana yori mo naho (2006) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Sword of Desperation / Hisshiken torisashi (2010) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Love and Honor (2006) | Japanonfilm