Machiko Kyo as the whipwielding Black Lizard

Black Lizard is a caper/melodrama unlike almost anything you are likely to find in American or European films.

Black Lizard, here played by Machiko Kyo, is Japan’s greatest jewel thief with her eyes set on the largest diamond in the world. But instead of a traditional mystery of the perfect crime, we have a plot line out of Dornford Yates or Sax Rohmer, full of kidnappings, absurd disguises, people trapped inside furniture, secret islands, and a villain’s lair right out of a James Bond movie but made years before Goldfinger or Thunderball.

The villainess’s lair, where her examples of human perfection are taxidermied

The plotting is so complicated and so absurd that I won’t even begin to try to detail it. While it is certainly entertaining, what really makes the movie more than interesting to American eyes is the way it is filmed.

There is a strong strain in Japanese movies of what Americans would call “theatricality,” and Black Lizard taps into that in a flamboyant way. It is not at all unusual to find moments in Japanese films where characters step into a spotlight, scenes are bathed in strange colors, unrealistic settings and backdrops are used intentionally, unbelievable makeup or costumes appear in the most realistic moments, strange camera angles, and tone changes on a dime. Black Lizard has all of those, plus sudden outbursts of dance and song.

For example, the initial kidnapping attempt plays as a relatively straight melodrama, though all the camera angles are slightly tilted. When the plot is foiled, Black Lizard escapes by disguising herself as a man in neat sports jacket, pants, tie, and a hat right out of Mad Men. But instead of casually walking out among the crowd, she dances down the hall and out through the hotel lobby.  Just as suddenly, we’re back to melodrama but the guards at the jeweler’s home suddenly burst into song. But there is not enough dance or song to suggest this is a “musical” under any normal understanding of the term. It just suddenly appears out of nowhere and then disappears just as quickly. There is a great deal of glittering diamond in transitions, and once it is even used to separate a split screen conversation, reminding us of Topkapi or Arabesque, but again years before either. Looking backward, we see this as an imitation of Euro/American films, or one of those bits of exotica that can make us now feel superior, but the practices far precede the psychedelia or comic book elements of Modesty Blaise or Casino Royale.

Just as suddenly, we’re back to melodrama but the guards at the jeweler’s home suddenly burst into song. But there is not enough dance or song to suggest this is a “musical” under any normal understanding of the term. It just suddenly appears out of nowhere and then disappears just as quickly. There is a great deal of glittering diamond in transitions, and once it is even used to separate a split screen conversation, reminding us of Topkapi or Arabesque, but again years before either. Looking backward, we see this as an imitation of Euro/American films, or one of those bits of exotica that can make us now feel superior, but the practices far precede the psychedelia or comic book elements of Modesty Blaise or Casino Royale.

Black Lizard slinks her love to her captive in the sofa

Black Lizard is not an innovator of such non-realistic approaches to film. You can see similar theatrical practices as far back as some of the surviving silents and they would be adopted by some of the most highly regarded post-war film-makers — see, for just a few examples, Kinoshita’s Ballad of Narayama, Ichikawa’s Ten Women in Black, or Shinoda’s Pale Flower and Double Suicide — though usually without the song and dance. What is striking about Black Lizard is that it is mainstream entertainment, a star vehicle for Machiko Kyo adapted from one of the most popular writers of modern Japan, Edogawa Rampo, whose mystery thrillers hold a position similar to those of Agatha Christie or Arthur Conan Doyle in the popular culture.

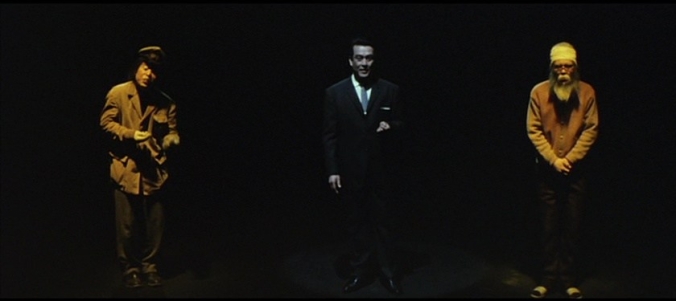

The detective introduces the story and his disguises in spotlights and double exposures

Looking back, we can also see this as early camp* or a parody of the old twenties/thirties melodramas,** hilarious to those in the know but confusing to the average film-goer. But I think this is probably a mistake. There are just too many other movies that use similar effects and techniques, sometimes for artistic effect, sometimes apparently for the joy of using them. It’s hard to believe that the general audience would in any way have been disturbed by them or thought them to be particularly highbrow.

The director here is Umeji Inoue, whose other work is unknown to me. Given the stylistic elements, it is perhaps no surprise that he spent a lot of time in later years in Hong Kong cinema. Minoru Oki plays Rampo’s great detective Akechi,*** so handsome and suave that Black Lizard falls for him (but still tries to kill him) when he is not donning some of the most absurd disguises in film history. But it really is a vehicle for Kyo and she seems to be enjoying herself immensely.

Though Rampo’s novel was published in 1934, the adaptation here comes with the finest of pedigrees. Yukio Mishima adapted it into a successful stage play in 1961, which obviously prompted its adaptation to the movies in 1962, and the screenplay is credited to Kaneto Shindo.

If you want to enjoy it as camp, feel free, but I think it is part of a tradition that is part of what makes Japanese movies so interesting. However you see its absurdities and exaggerations, it is certainly entertaining.

- * Kinji Fukasaku would push that particular envelope in a remake in 1968, where he adds neon nightclubs full of go-go dancers and a Black Lizard played by a male.

- ** Some of Vincent Price’s movies in the early seventies approach this kind of visual flamboyance, in particular The Abominable Dr. Phibes and Theater of Blood, while being clearly intended as send-ups of the super-villain genre.

- *** A series of at least eight movies featuring Akechi were made in the mid-fifties.

Pingback: Stakeout / The Chase / Harikomi (1958) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Ballad of Narayama / Narayama bushiko (1958) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Killers on Parade / My Face Red in the Sunset / (1961) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Gate of Flesh (1964) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Tokyo Drifter / Tokyo nagaremono (1966) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Black Lizard / Kurotokage (1964) & Black Rose / Black Rose Mansion / Kuro bara no yakata (1965) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: D-Slope Murder / Murder on D Street / D-Zaka no satsujin jiken (1998) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Cat’s Eye (1997) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Rampo (1994) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: K-20: The Fiend with Twenty Faces / K-20: Kaijin niju menso den (2008) | Japanonfilm