Blue Spring takes us inside a boys’ high school in the last weeks before graduation, and it is unlike any Japanese school we have seen on film. The first thing we see is an adult desperately running away across the school playing field, with a gang of boys chasing after. The hallways, toilets, and stairways where most of the movie takes place are covered in graffiti, students wander in and out of class at will, and when they are in class pay little or no attention to the teachers. There is no sign of the traditional deep bond between students and their sensei. When one single girl appears at the gate to the grounds waiting for a boy, dozens of boys all over the school leave their studies to hang out the windows and yell and wave at her. Student life is ruled by a gang of seniors, who bully younger students and beat up anyone who challenges their eminence. Though all the boys go home each day, we never see parents or families or home scenes, so we have no idea where their families reside on the social scale or even where the town is, but it is definitely not a slum school, not a Japanese version of Blackboard Jungle. There is a music room, a large playing field, a swimming pool, and a remarkably well-maintained flower garden. At the end of the school day the gang separates and as far as we are shown have no activities together outside of the school; they do not terrorize local businesses or beat up other kids on their way home.

Blue Spring takes us inside a boys’ high school in the last weeks before graduation, and it is unlike any Japanese school we have seen on film. The first thing we see is an adult desperately running away across the school playing field, with a gang of boys chasing after. The hallways, toilets, and stairways where most of the movie takes place are covered in graffiti, students wander in and out of class at will, and when they are in class pay little or no attention to the teachers. There is no sign of the traditional deep bond between students and their sensei. When one single girl appears at the gate to the grounds waiting for a boy, dozens of boys all over the school leave their studies to hang out the windows and yell and wave at her. Student life is ruled by a gang of seniors, who bully younger students and beat up anyone who challenges their eminence. Though all the boys go home each day, we never see parents or families or home scenes, so we have no idea where their families reside on the social scale or even where the town is, but it is definitely not a slum school, not a Japanese version of Blackboard Jungle. There is a music room, a large playing field, a swimming pool, and a remarkably well-maintained flower garden. At the end of the school day the gang separates and as far as we are shown have no activities together outside of the school; they do not terrorize local businesses or beat up other kids on their way home.

In Japan, graduation occurs at the end of the winter term, so the cherry blossoms are appearing along the road outside the school grounds, promising a new life for all the graduates. Some of them may in fact find university entrance or good jobs, for in the background of our principal characters we see other students paying attention and taking notes in class and generally going about the business of staying out of the way of the ruling gang. It is also the end of the year for the teachers, who at this point, like many American teachers facing classes of seniors in the month before graduation, seem to have given up on anything but finishing the syllabus. We only see the history and math teachers, listing dates or working out formulae on the blackboard without any real interaction even with the students who are paying attention, which perhaps over-emphasizes the drone aspect of their work.

Blue Spring brought Toshiaki Toyoda to considerable prominence in the Japanese film industry.

Like so many of the younger directors coming into prominence at this time through their violent films (Miike, Aoyama, Sabu, Tsukamoto, Mochizuki, etc.) he knows and uses the full modern international film vocabulary, from slo-mo to time-lapse, long take to quick cuts, POV to high and low angles, and touches of fantasy and flashbacks. Since the cherry trees are always in blossom outside the gates, and cherry trees bloom for a very short time, we are completely unsure of the detail of the timeline. Sometimes it seems we are covering a full year, at others only a single semester.

I can not recall such a portrait of a Japanese high school ever, even in the Sun Tribe and Japanese New Wave era of disaffected youth. In the closest similar school seen in Kids Return, the two bullies are outsiders and the rest of the students, though not real university material, at least pretend to be studious and respectful. And, it should be noted, the gang’s activity in the classroom is confined to merely ignoring the teachers, eating lunch or talking to each other, sitting on rather than at their desks, and wandering in and out at will, rather than actively interrupting the lessons.

The gang is led by Kujo, played by the feminine-faced Ryuhei Matsuda* of Gohatto,

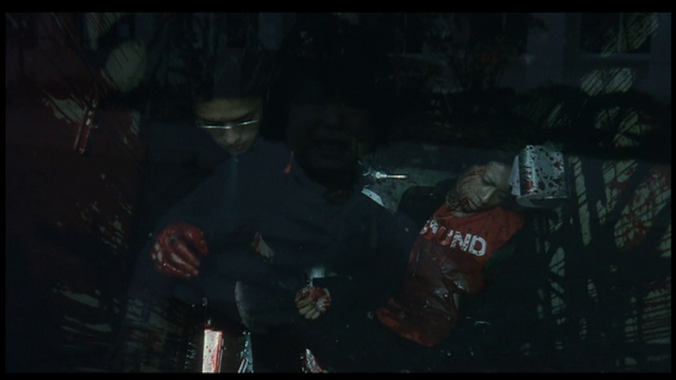

a most unlikely look for the school’s biggest gang leader. He is not the toughest, largest, or cruelest but the most daring and unpredictable. Sneaking up onto the roof, eight boys in the group play a game in which they balance on the safety fence at the edge and clap their hands as many times as they can before having to grab back on to save themselves from falling. Down to the final two, Kujo manages eight while his best friend since childhood Akio gives up after seven. Kujo at times seems utterly indifferent to his position, while the others in the group do plenty of bullying of other kids to take advantage of their relationship to him. However, when he is challenged by the previous top dog, he breaks his nose and later will use the baseball bat to great effect, so he is capable of brutal violence himself.

Since we see only standard high school uniforms that have been worn by Japanese boys since before WWII, and the one girl is in the old-style sailor suit rather than the plaid skirt Kogal look, Blue Spring seems to exist in no specific time. It was adapted from a group of short stories by Taiyo Matsumoto published in manga form in 1993, so they could have been about his own high school experiences before he dropped out in the early eighties; the occasional cars outside the gates belonging to yakuza are the boxy imported American cars worn as a badge by yakuza of that earlier era, and we even see a low-rider Chevrolet convertible bouncing up and down. No one has a cellular phone (though a counselor does have a computer, but of a size that could have come from the eighties and suggests no internet connection). Yet the movie reflects a concern in society at the turn of the century that something had gone wrong with teenagers, seen most similarly in the ninth graders’ physical attacks on a teacher in Battle Royale. It is also reflected in the behavior of teenagers seen in movies as varied as Ringu, Suicide Club, Bounce Ko Gals, or Kamikaze Girls (although as I type this, I realize that most of those were concerned with changes in attitudes of girls rather than boys and dealt with ninth or tenth graders, not seniors).

No one has a cellular phone (though a counselor does have a computer, but of a size that could have come from the eighties and suggests no internet connection). Yet the movie reflects a concern in society at the turn of the century that something had gone wrong with teenagers, seen most similarly in the ninth graders’ physical attacks on a teacher in Battle Royale. It is also reflected in the behavior of teenagers seen in movies as varied as Ringu, Suicide Club, Bounce Ko Gals, or Kamikaze Girls (although as I type this, I realize that most of those were concerned with changes in attitudes of girls rather than boys and dealt with ninth or tenth graders, not seniors).

Rather unexpectedly, sex does not raise its head. It is a boys-only school, but even so, there is no discussion of girls and the graffiti has none of the big boob women or pictures of penises found in similar school bathrooms throughout the world.

Some of the boys in the gang eventually get drawn to the yakuza, a traditional place for rootless young men to end up. One is eternally distraught over the fastball he threw in the game that lost the school team a chance at the national tournament. Yukio is the most cryptic. When the counselor tries to get some kind of idea about his plans, he only answers blankly, eventually leaving after giving the peace sign. Soon after, when another boy tries to recruit him for the yakuza in the toilet, Yukio stabs him to death.

Yukio is the most cryptic. When the counselor tries to get some kind of idea about his plans, he only answers blankly, eventually leaving after giving the peace sign. Soon after, when another boy tries to recruit him for the yakuza in the toilet, Yukio stabs him to death.

But the real challenge for Kujo comes from Akio, who had been Kujo’s closest friend since fourth grade. Something snaps and he decides to form his own gang, which is much more openly violent as it roams the hallways. This brings out Kujo’s one real moment of violence, and after Akio’s humiliation in face to face fisticuffs and the destruction of his small band of rebels, he goes onto the roof alone to play the clapping game, failing at last when he attempts thirteen, with Kujo racing to try to catch him before he falls.

It’s been a long time since we had a Japanese movie so utterly driven by rock ‘n’ roll, though none of the characters plays electric guitar. The garage punk sounds of TMGE** assault the senses from the very opening, just as similar two and three chord high volume punk drove Throw Away Your Books and Burst City. This, as much as Toyoda’s direction and the graffiti on the walls, gives the movie its sense of total social collapse.

* Matsuda was the son of Yukasu Matsuda, though you would never guess by looking at him. Thus he was part of the long Japanese tradition of young actors carrying on the family trade and would sustain a substantial career even as he grew older.

** Ironically, the end of Kujo’s gang was mirrored in the band itself, which had been very active throughout the nineties but broke up shortly after this movie was released. Whatever the names used, this punk-like sound always lurked in the underground of rock, sliding into the mainstream from time to time in groups like Nirvana, also a nineties phenomenon, but with small club followings such as can be seen in Japan in movies such as Drive (2002).

Pingback: Dororo (2007) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Linda Linda Linda (2005) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Ping Pong / Pinpon (2002) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Blue Light / Ai no hono-o (2003) | Japanonfilm