The moon child of the title is Kei, who is no child but is instead a vampire in the Dracula sense – he drinks blood, is eternal, and can only be destroyed by sunlight. First seen in Tokyo at the start of the millennium, he reappears throughout a sci-fi future life that concludes in the year 2045. But the movie is really about Sho, whom we first seeas a young teen in 2014 in a Chinese free-trade-zone city called Maleppa, where immigrants from all over the world have congregated in search of a better life.

The moon child of the title is Kei, who is no child but is instead a vampire in the Dracula sense – he drinks blood, is eternal, and can only be destroyed by sunlight. First seen in Tokyo at the start of the millennium, he reappears throughout a sci-fi future life that concludes in the year 2045. But the movie is really about Sho, whom we first seeas a young teen in 2014 in a Chinese free-trade-zone city called Maleppa, where immigrants from all over the world have congregated in search of a better life.

Sho is Japanese, for the city has drawn an enormous number of people from Japan, which has fallen on hard times. As a youngster, he and his buddies rob people’s cars by pretending to have been hit by the driver and stealing whatever is inside while the driver checks on the victim. In one escape, he finds Kei in an abandoned factory but he is not shocked when he sees Kei feeding. Fast forward eleven years, and Sho and his buddies along with Kei are a gang raiding other gangsters, where they run into the third principal character Son, a Chinese young man who is after the same gang in revenge for their raping his little sister.

Soon, all of them become a gang of robbers until we again fast forward into a yakuza/tong war that eventually leaves only Sho, since Son has changed back to the Chinese side even though his little sister married Sho. Kei is back in Japan awaiting execution for four murders, though how they expect to do that for a man who cannot die is never explained — he says they should just take him outside, but no one listens to him.

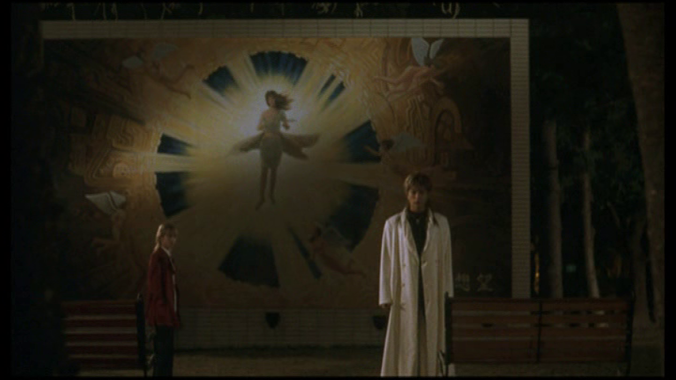

As the brief summary suggests, the movie is stylistically all over the place. The gun battles are right out of the Hong Kong world of Johnnie To and Ringo Lam, the vampire lore out of the Dracula stories (but without a cape) with a touch of Hong Kong acrobatics to show Kei’s super-powers, Sho’s adult appearance is out of The Matrix, dodging bullets in a white coat instead of black. The seemingly endless ending is out of the most sentimental strain of turn-of-the-century Japanese movie-making, and we finish with an unusual twist on the traditional love suicide.

The gun battles are right out of the Hong Kong world of Johnnie To and Ringo Lam, the vampire lore out of the Dracula stories (but without a cape) with a touch of Hong Kong acrobatics to show Kei’s super-powers, Sho’s adult appearance is out of The Matrix, dodging bullets in a white coat instead of black. The seemingly endless ending is out of the most sentimental strain of turn-of-the-century Japanese movie-making, and we finish with an unusual twist on the traditional love suicide.

Nevertheless, the movie is interesting, even engrossing, at least until it starts the tear-jerking, with the various set pieces spectacularly well handled by Takahisa Zeze without the slightest hint of his pinku background and a strong sense of the power of friendship, which ultimately becomes more powerful than love.

Despite Japan’s long tradition of horror movies, the vampire had never really taken hold. There had been three or so Hammer-style modern-dress Dracula movies in the early seventies, but since then I can find nothing until Moon Child. Kei here is not a figure of horror but essentially treated as a sympathetic figure, a man alone and unchanging in a world where everyone he loves keeps aging and changing. For the most part, in scenes we see, he drinks his blood from people who are already dying, usually from gunshot wounds, though the killings that lead him to Death Row may have been actual vampire murders. There are long spells when he refuses to feed, when others comment on how weak he has become. Horror is not the purpose of the movie.

In a way, it is an inversion of Swallowtail Butterfly, depicting the difficulties of the immigrant life but with the Japanese moved from the top to the bottom rung of the social scale. Now the usually law-abiding, conformist Japanese are forced by their position to live in the slums alongside other aliens or to become gangsters. Filmed in Taiwan with a multi-cultural cast, it jumps around from Japanese to Mandarin to Taiwanese to Cantonese with some dialogue in English as well, probably making it easier for English speakers than for its original audience to watch because everything is in subtitles.

It is also an inversion of the usual Japanese “idol” movie, with not one but three music stars, all of them male. Sho is GACKT (the capital letters are his performing name), by this time a major solo music star able to fill Japan’s largest arenas.

Kei is HYDE, the lead singer for one of the most inventive and well-known rock bands in Japan. Son is Leehom Wang, actually a Chinese-American with music degrees from American schools, who had become one of the most popular singers in Taiwan and then later throughout East Asia, including major sales and performances in mainland China. As with most of the female idol movies, none of them sing on screen, though they all contribute songs to the music from many sources used on the soundtrack. GACKT wrote the original story, which perhaps explains why he gets so much screen time. Unfortunately, try as he might, Zeze can’t really disguise the fact that none of the three are actually actors, no matter how much the dialogue is limited.

Nevertheless, until we reach the scene of a brain tumor for Sho’s wife,* it is a fascinating, often exciting movie that whips along with great invention, a real triumph of style over substance.

* Jasper Sharp (Behind the Pink Curtain) has noted that Zeze’s pinku movies usually have a similar structure, building to their most violent climax in the middle, then followed by a slow fading of intensity to the ending. I haven’t seen enough of those films to agree or to argue, though Raigyo certainly has that kind of unusual dramatic structure. Sharp relates this to a Buddhist way of thought, which again I do not feel qualified to comment on, but it is certainly worth consideration here. (I might add that this is not unique to Zeze’s nor to Buddhist films. Shakespearean structure often builds the drama to a violent climax in the middle, then sort of starts over, as in Hamlet, Macbeth, Lear, Cymbeline, Winter’s Tale, etc.) Nevertheless, the sudden brain tumor, the hospital scenes, the wife’s confusion of Sho for Kei, the little orphan girl left behind, all seem to me to be more intended to turn an over-the-top example of the Miike school of Japanese film into a mainstream tear-jerker more suitable for an “idol” movie than to project a Buddhist search for peace.