Made in a time when American and Japanese movies and society often seemed to be merging, Doing Time reminds us that the Japanese still do things differently. Based on the autobiographical manga by Kazuichi Hanawa, it follows the life of the sixty-ish Hanawa as he serves a three-year term in prison.

Made in a time when American and Japanese movies and society often seemed to be merging, Doing Time reminds us that the Japanese still do things differently. Based on the autobiographical manga by Kazuichi Hanawa, it follows the life of the sixty-ish Hanawa as he serves a three-year term in prison.

Unlike in prison movies made the world over, there are no riots, no brutality, no murders in the showers, no attempted jail-breaks, no drugs smuggled in, no one on Death Row, in fact no “drama” at all. If such a thing is possible to conceive, it is a shomin-geki, set in a prison rather than among lower-level salarymen, with its constant humiliations and yet a light humorous touch.

Though the prison itself is in Hokkaido, this is no Abashiri prison with hard labor chain gangs working in the snow and desperate escapes. Apparently filmed during the warmer seasons, it only shows us snow on the mountains and falling outside the window, with all the outdoor scenes relatively sunny and mostly on the bare earth of the prison grounds.

As with earlier glimpses of prison life, there are still five men in the same cell – five animals in a pen, as an intertitle has it – but with no grudges or fights beyond some repetitive teasing. As the oldest man in the cell, Hanawa (Itami regular Tsutomu Yamazaki) narrates all this as both a man learning the ropes and an external analyst.

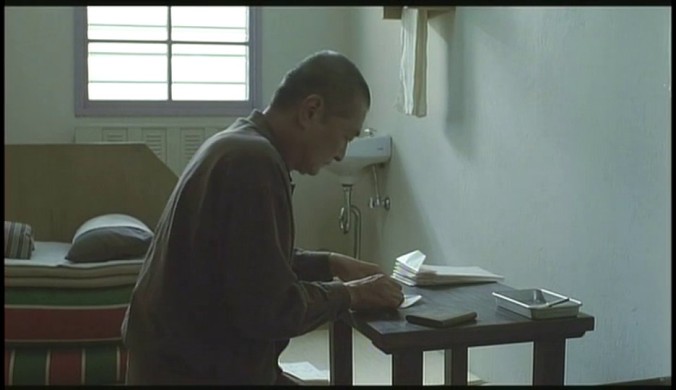

In fact, it is a life of perpetual repetition. Everything is regimented, down to requests for permission to go to the toilet even inside one’s own cell. The prisoners are awakened at the same time, clean the cell and store their futons, and sit in a row to await roll call and breakfast. Afterward they are marched to their work, making what appear to be wooden boxes for tissue boxes, with lunch provided at the work. They are given exercise periods, again regimented and done all together, like military calisthenics, and even baseball games, but these too are regulated by the clock, stopped by the guards before they are over. Dinner is back in the cell, and afterward TV or reading. They can keep a diary, but only at the small table, never while lying in bed. Baths come on a regular basis, still timed rigidly, and small groups are allowed a movie night on a regular schedule. Saturdays and Sundays are days off from work, but spent mostly inside the cell. (As far as I can tell from films, most workers in Japan still did not get Saturday off at this time, so it is unusual to see it in a prison setting.)

The guards shout commands, but they are completely unarmed. We never see even a baton. They are as rigidly regimented as the prisoners and we never see them except as Hanawa sees them.

Hanawa’s crime was illegal possession of a firearm. He and some friends liked to play at war games, but this being Japan they have to build their own guns and basically fire caps, not even blanks. One has built an exact copy of the gun that shot Robert Kennedy, but Hanawa is the hero of the group because he has manufactured an exact replica of Dirty Harry’s pistol. How all this came to the attention of the authorities is never explained, but Hanawa is given three years. Others in his cell have actually killed people – one in semi-sell-defense, another as a yakuza (who is there only because one of his group turned himself in to the police, implicating everyone involved). We never really learn what the other two have done, though one is wealthy on the outside and spends his evenings poring over catalogs of the most expensive shoes.

How all this came to the attention of the authorities is never explained, but Hanawa is given three years. Others in his cell have actually killed people – one in semi-sell-defense, another as a yakuza (who is there only because one of his group turned himself in to the police, implicating everyone involved). We never really learn what the other two have done, though one is wealthy on the outside and spends his evenings poring over catalogs of the most expensive shoes.

At one point, all the men in the cell are put into solitary, which Hanawa actually finds he likes. But again, this is different from solitary in most American prisons. The room itself is light and airy, and he is given a job, folding and gluing together paper bags for pharmacies. He loses himself in the repetitive nature of the job, focusing all his attention on perfection and speed. He even chooses to do his exercise period in his cell rather than outdoors, where the men in solitary still see no one else, and he loves the spa-like experience of his solitary bath time.

Food becomes the focus of all experience. Unlike in American prison films, the prisoners like the food. It is varied and well-prepared, but they can discuss the last meal or the next one for hours if given the time. Bread day is a highlight of the week, with long debate over the value of the margarine and whether it should be used only on bread or also added to beans. When one of the men goes to see the movie and they ask him what it was like, he doesn’t talk about the movie (Kids Return) but about the taste of each chocolate covered cookie and sip of canned cola they are given. Through these kinds of repetitious jobs and discussions, the movie becomes another example of that uniquely Japanese attitude toward the pleasure to be found in the appreciation of small things, like sweet red beans or properly folding ones pajamas or making perfect bags.

For an American viewer in particular, the surprise is how easily the prisoners accept the regimentation. There is no Steve McQueen type who refuses to bow to orders, even in solitary. The guards carry no weapons, even though the men we see work with sharp knives when decorating their wooden boxes, and threaten no physical punishment. Even in the Japanese military films, many of the recruits have to be beaten into submission. Here, each prisoner knows he has done something wrong and accepts that, and yet finds not punishment but a kind of pleasure in the prison routine.

The prison is operated for neither punishment nor rehabilitation; there are no counselors or psychologists, just as there are no guards who slam prisoners against the wall. No visitors are ever mentioned, nor letters from home read, yet only one man in the cell talks about missing his family. No one claims he was framed, no one insists the court was biased. Each man knows he is guilty of something and accepts that this is what is demanded of him as a result. The rehabilitation came with their confession in court, and their punishment is simply separation from the rest of society.

Kinema Junpo ranked it second only to Twilight Samurai in its year. Directed by Yoichi Sai, Japanese-born with Korean parents, it has some of that anthropological distancing of a society observed by someone who is still not quite fully integrated. In many ways, it is a sociological document, yet holds interest as a movie precisely because it is so detailed yet so unexpected, presented with a light touch that is not quite comic yet not in the least depressing, much like Sai’s earlier All Under the Moon .

I was trying to figure out whether this was punishment or rehabilitation. The guard who supervises the work sessions is called “teacher” in the subtitles, which implies training ; but if this is punishment, then the relative comfort of their lives makes it clear that the one thing they cannot have is freedom itself. The movie is a very interesting experience, especially in the light of the cruelty and violence of some other Japanese films.

LikeLike

Pingback: Dororo (2007) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: My Grandpa / Watashi no guranpa (2003) | Japanonfilm