There have been many Japanese movies about sex and the teen-aged girl, but few are as disturbing to watch as Girl of Silence. Shizuko is 14 when her mother brings home a new man. She has her first sexual experience with a boy in her school class, and very awkward it is for both of them; nevertheless, she becomes pregnant. The new man, who insists on being called Father, decides she must be punished for this, even before she gets an abortion, and again whenever she disobeys him. The punishment is that he rapes her, which she endures in silence each time it happens. From the first, her mother knows this is happening, even before Shizuko confronts her with it. Eventually, at age fifteen, Shizuko manages to drive the man away and also leaves home to go to Tokyo to become a manga artist.

There have been many Japanese movies about sex and the teen-aged girl, but few are as disturbing to watch as Girl of Silence. Shizuko is 14 when her mother brings home a new man. She has her first sexual experience with a boy in her school class, and very awkward it is for both of them; nevertheless, she becomes pregnant. The new man, who insists on being called Father, decides she must be punished for this, even before she gets an abortion, and again whenever she disobeys him. The punishment is that he rapes her, which she endures in silence each time it happens. From the first, her mother knows this is happening, even before Shizuko confronts her with it. Eventually, at age fifteen, Shizuko manages to drive the man away and also leaves home to go to Tokyo to become a manga artist.

The story is adapted from an autobiographical novel by the manga artist Shungicu Uchida. By this date, she had become widely known for the extremely popular manga Minami-kun no Kobito, about a girl who shrinks so that she can fit in the pocket of her best friend, which had been adapted for TV twice already by the time her novel came out (and would appear at least twice more). Thus, the appearance of the novel caused quite a sensation, not least because of its Japanese title (pronounce the romanji and you will know why its title was changed for American and European DVD release).

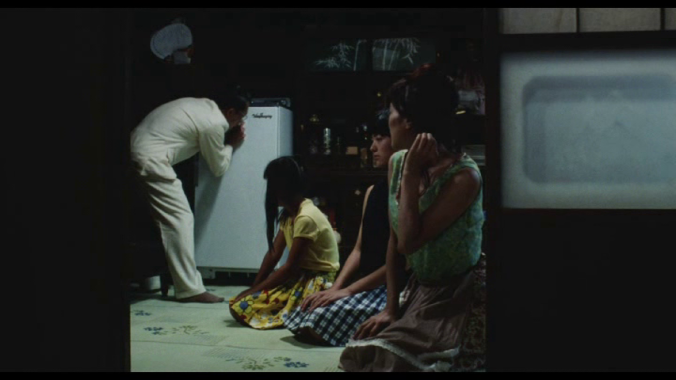

The movie is set in 1968 in Nagasaki, three years after the real father of Shujiko and her little sister Chie had stormed off. Her mother is a bar hostess and one day she brings home a new man. Initially, the girls are not too concerned, because they expect him to leave “just like all the others.” Mom is actually his mistress, for he often goes to stay at another home, but he is a very straight-laced and traditional man who insists that Mom quits her job, that the girls always address him as Father, and that all the traditional greetings should be given when he arrives, even if he has to stand outside the door repeating “I’m home” several times until everyone inside is kneeling to bow and offer him the proper response. When he eats with them, he holds out his bowl when it is empty and continues to hold the arm out straight until one of the females has returned with a newly filled bowl. He even changes Chie’s name to Chieko. He thinks manga are low class and certainly not something for a girl and thus often destroys Shujiko’s drawings.

Outside of traditional respectability, his one passion is the new refrigerator he has installed when he moves in, often going straight from the doorway to polish it. His constant mantra is that this is a “decent” household. Thus, it is more than a little shocking when we see him stripping off to crawl into Shujiko’s bunk bed and even more shocking when we see Mother keeping Chie outside while Shujiko is “being punished.”

Shujiko takes the rapes in complete silence. Finally, when she talks to her mother, she is told that she must be the real pervert for sleeping with mother’s “husband.” The 15-year-old Mami Nakamura has no actual nude scenes as Shujiko, with even her first experience with the teenaged boy done in her school uniform, so we are not in exploitation territory here. The seriousness and respectability of the movie is underlined by the casting of Kaori Momoi as Mother. Despite her many awards for other movies, I don’t think I have ever seen her play any more complex role.

When the three females are alone, they are a happy and playful group, but Mother still has to feed herself and the kids. As we have seen in so many movies of the fifties and sixties, there are only three options available to an unmarried woman (or a woman whose husband has deserted her) – bar hostess, actual prostitution, or becoming a mistress. Given “Father’s” rigid traditional attitudes – he doesn’t even allow Mother to accompany him and the girls to a festival because her place is in the home – it is hard to know how they hit it off. We know that businessmen and salarymen were required to spend a great deal of time in bars with clients, so it must have been there that he saw her, but no mention is made of their meeting and any sex they had before he arrived occurred in love hotels. When we see her in the bars, she is a lively companion, loving the dancing and the music and the company in general, but not seductive or suggestive.  In her hostess dress, she is a sexy creature without ever openly offering sex, so we can see why any man might be attracted to her. He is most definitely not a similar personality, but there is no hint that he chose her for wild nights of sex to escape a more traditional marriage. The children never hear noises in the night and his very insistence that he will be seen and treated as Father indicates that he expects the reconstruction of traditional family relations even in the bedroom.

In her hostess dress, she is a sexy creature without ever openly offering sex, so we can see why any man might be attracted to her. He is most definitely not a similar personality, but there is no hint that he chose her for wild nights of sex to escape a more traditional marriage. The children never hear noises in the night and his very insistence that he will be seen and treated as Father indicates that he expects the reconstruction of traditional family relations even in the bedroom.

The final crisis for the group comes when he loses control completely and begs Shizuko to run away with him. She of course refuses, he nails her into the outhouse, and when released she manages to short out and blow up the sacred refrigerator.

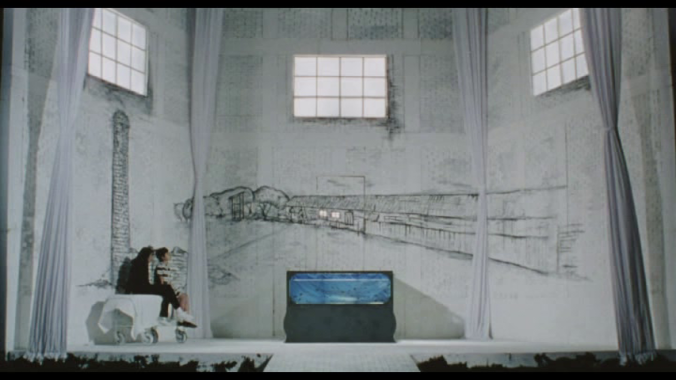

For Shizuko, her drawings are both her dream and her escape. Skipping class to draw in the school infirmary, she is visited by a strange boy whose hair color changes each time we see him. Together they escape into the fantasy settings that she has drawn, where they talk — no romance is even suggested — which take us back to the openly theatrical insertions found in so many earlier movies, still seen in the nineties but more rarely.

This is the first of only three movies directed by Genjiro Arato, an Independent’s Independent of his time. Arato had produced Suzuki’s Zigeunerweisen and, when no distributor would take it, began showing it in tents around the country; he had also produced the surprise critic’s favorite Knockout. He is not credited as a producer on Girl of Silence (that is first-timer Miyoshi Kikuchi), but the vision and the detail of the performances suggests someone who could have been a major director had he so chosen. There is also immaculate period detail, not always common in Japanese movies, with production designer and costumer untranslated in the subtitles, from the dresses to the formica top of the chabudai to the tiny taxi that takes away Shizuko’s father to the accordion on the soundtrack so often heard in post-war movies.

Its subject matter is shocking but not unheard of in earlier Japanese movies, and Shizuko is portrayed as a true survivor, scarred but not beaten. Her dreams are of a future success as an artist, not of revenge for what has happened to her. It is a sordid story but never presented in a sordid manner. There were a lot of pretty good movies in 1995, but it is nevertheless surprising that Girl of Silence appears to have been completely ignored by Japanese critics. It should not continue to be ignored.

Pingback: Face / Kao (2000) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: An Adolescent / Shojo/ Shoujyo (2001) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Always: Sunset on Third Street / Always san-chome no yuhi (2005) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Akame 48 Waterfalls / Akame shijuya taki shinju misui* (2003) | Japanonfilm