Heat After Dark actually occurs in the daytime, over one day. The first film of Ryuhei Kitayama, who would become a cult favorite with his later Versus and Azumi, it is all action. A pair of feet walk into a room and meet another pair of feet, with the feet of a body in the background. The body belongs to a yakuza who hit his head in an argument over a debt owed by Goto (Kazuma Suzuki), or so Goto claims. He calls for help from Reiji (Atsura Watabe) who is a friend, not a relative, as far as we can tell. They load the body into Reiji’s car to bury it in Kitiyama, an abandoned town that will soon be flooded by a new dam. They are stopped by a policeman who demands they open the trunk, but when they do, the body is gone. The yakuza has slipped out somehow and soon begins firing on them. Goto has in fact been smuggling guns for the yakuza he thought he had killed, so the argument was about who got the money for the sale, which hasn’t happened yet, so we will actually have the part of a heist movie in which the partners fall out and kill each other, now seen before they get the money rather than after, with Reiji, the policeman, and some of the yakuza’s gang all caught in the middle.

Heat After Dark actually occurs in the daytime, over one day. The first film of Ryuhei Kitayama, who would become a cult favorite with his later Versus and Azumi, it is all action. A pair of feet walk into a room and meet another pair of feet, with the feet of a body in the background. The body belongs to a yakuza who hit his head in an argument over a debt owed by Goto (Kazuma Suzuki), or so Goto claims. He calls for help from Reiji (Atsura Watabe) who is a friend, not a relative, as far as we can tell. They load the body into Reiji’s car to bury it in Kitiyama, an abandoned town that will soon be flooded by a new dam. They are stopped by a policeman who demands they open the trunk, but when they do, the body is gone. The yakuza has slipped out somehow and soon begins firing on them. Goto has in fact been smuggling guns for the yakuza he thought he had killed, so the argument was about who got the money for the sale, which hasn’t happened yet, so we will actually have the part of a heist movie in which the partners fall out and kill each other, now seen before they get the money rather than after, with Reiji, the policeman, and some of the yakuza’s gang all caught in the middle.

But all of this information is pieced together as we go. The movie lasts less than an hour,* since Kitayama has simply skipped any exposition and gone straight to the action. It is a manga come to life, except that it is not based on a manga. All of the affair could be ignored, written off as a vanity project, except that there is no doubt that there is an enormous amount of talent in evidence, much more than in, for example, Haruki Kadokawa’s vanity projects made with far more money. There is some self-promotion to be found, since the project was produced by Watabe, presumably to change his image after A Quiet Life, and the movie is written, directed, and edited by Kitamura. Nevertheless, despite the gunplay, the actual gore is limited, closer to a Kitano movie than to the excess or absurdity to be found in Miike’s films, while the pacing is superb and the action has great variety and an energy not found in Kitano’s approach. There are moments of odd humor as well. It’s not a movie made purely for blood and guts exploitation. Every shot is beautifully composed, presumably by Kitamura as well since the credited photographer had no other credits for another decade. It never looks like a group of people just went to an abandoned factory and said “Let’s make a movie.”

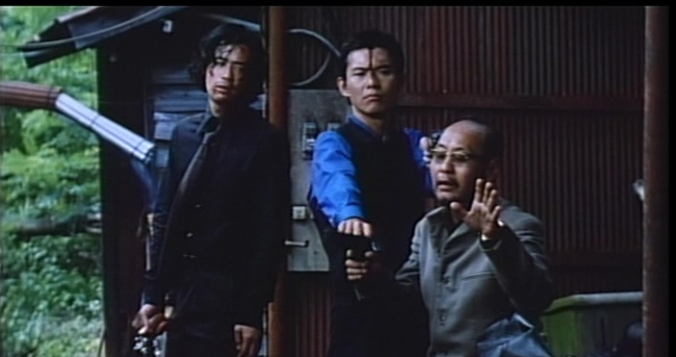

Because we don’t have any real development of characters or motivation, the movie is an exercise in style, in pure movie-making for its own sake. Yet this is presented within the classic traditions of Japanese films – careful compositions, low angle camera, middle distance shots, elliptical motivation and emotion, face to the camera positioning. Perhaps the best way to discuss this is just to show some screen captures.

Even more striking is an insanely weird music score provided but not composed by Moichi Kuwahara. Opening with a weird guitar arrangement of “The Shadow of Your Smile,” it progresses through Arabic chants to Tuvan throat singing from the Siberian band Yat-Kha that provides a strange sense of both other-worldliness and suspense to the scenes on screen and arguably makes them seem better than they are.

Very few first movies I can think of have shown this kind of technical skill from the director. (Citizen Kane is the obvious benchmark, of course, but it was made with the resources of a Hollywood studio and the aid of one of the greatest cinematographers in film history, not to mention an actual script.) Yet Heat After Dark is all surface skill. From the later Kitamura movies I have seen – Versus, Azumi, the 50th anniversary Godzilla – he has never learned or desired to use that skill for anything other than surface action, simply presented at greater length. Still, the movie serves as another marker in the turn toward gun violence as a staple in Japanese movies during the nineties.

* Japan made many features of this length in the post-war era, but they were either intended for younger audiences or as parts of double features or both. Similarly, a number of pinku films were under an hour but also intended to be part of double or even triple features, and a lot of the film-school generation of the eighties started with short features like this as well. But by the late nineties, the double feature seems to have disappeared in Japan, just as it had in the rest of the world, so who might have actually shown this movie at this length is pure guess work. IMDB dates it at 1996 but shows no actual release date, the copyright says 1997, and Alexander Jacoby says 1999. Its wide-screen format, often distant visual placement and wide separation of actors suggests it wasn’t made for TV or direct-to-video, though some widescreen TV was available in Japan by the late nineties. Thus, who actually saw it and when remains a mystery, though obviously someone did or Kitamura would not have had a career.

Pingback: Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl / Samehada otoko to momojiri onna(1998) | Japanonfilm