Ironically, there is no cure to be found for the question continually asked in Cure – Who are you? This marks it as one of the most disturbing, significant, and haunting horror films from any nation. Like most of us, Takabe answers the question with his job – “I am a detective” – but the questioner refuses to accept that as an answer.

Ironically, there is no cure to be found for the question continually asked in Cure – Who are you? This marks it as one of the most disturbing, significant, and haunting horror films from any nation. Like most of us, Takabe answers the question with his job – “I am a detective” – but the questioner refuses to accept that as an answer.

Takabe is investigating a peculiar set of serial killings, all of which are signed, so to speak, with an X carved in the victim’s neck but which are all carried out by different people. The police easily arrest each killer, but he or she has no explanation other than that it seemed to be the right thing to do at the time, and none have any connection to the others. Takabe thinks it might be a case of copycat killings, except nothing has been in the news, so they search for clues in TV, movies, or fiction, but no similar cases can be found. Takabe even considers the possibility of a hypnotist, but his psychiatrist friend tells him that no hypnotist can make a person do what they do not really want to do. That, as it turns out, is what makes the ultimate solution one of the most disturbing in film history. .

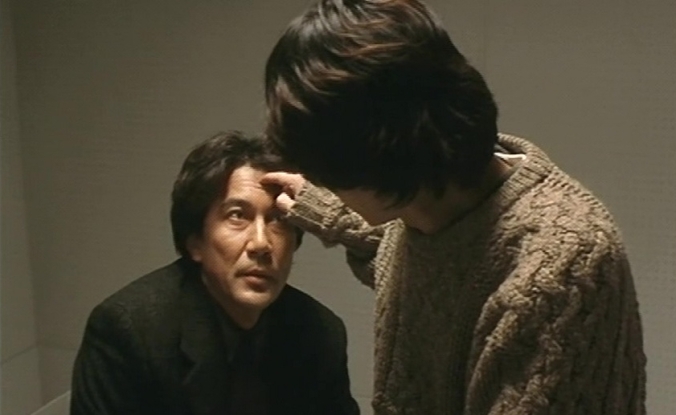

The audience is given the connection before Takabe finds it, but it still seems inexplicable. All the killers have met Mamiya, a young man who is (or seems to be) so completely amnesiac he can’t remember what he just heard, much less his own name or past. What he does do is continue to quietly ask each person he meets The Question. He picked up a form of hypnotism in his college studies before he himself went crazy, but it is not a hypnotism that can make a person act like a chicken on stage. Rather, it releases the deepest resentments, the feelings we know can never be admitted in society or the society itself will collapse. Each time we return to Mamiya, we see a little bit more about his question sessions until at last we see a meeting in detail. This, as it happens, is a visit with a female doctor in which his questions lead her mind back to all of the hurdles she had to face as a woman when she tried to become a doctor, and after a few scenes of apparent normality we find her in a men’s restroom slicing the neck of a strange man she has just killed and beginning to peel off his face.

This is the most explicit and gruesome scene in the movie, which otherwise confines the blood to the aftermath of the crime, if it is seen at all. Cure is an intellectual horror movie, but not in the sense of “Turn of the Screw,” for example, in which reason and the supernatural are at war. Rather it is intellectual in the sense that it first requires us to fill in the gaps of the mystery and then once we have done so, it leaves us with a sense of unease about everything we have accepted about society and about ourselves.

Takabe is the one person who appears to resist Mamiya, yet somehow before the movie is done his best friend, Mamiya, and his mentally-ill wife all end up dead, the friend with an X on the wall and the wife with the same X across her throat while she is in an asylum. The most cryptic and yet disturbing scene in the movie is the one in which nothing happens; Takabe finishes his meal in a restaurant and the camera follows the waitress who has cleared his table in the far distance as she goes about the rest of her routine across the room but picks up a knife as she does and we go to the credits.

Much has already been written about Cure, and I debated writing about it since I try to comment in this blog on lesser known movies, but the movie seems so important as well as unique that I could hardly resist after a re-watch. Dissertations could be (and for all I know may have already been) written about its analysis of the social isolation, the lack of personal fulfillment, and the loss of the Self in modern urban society. Those themes would become particularly prominent in turn of the century Japanese movies, particularly those devoted to young characters such as Suicide Club, Ringu, Battle Royale, or Pulse, but in a sense they have been a running theme of Japanese movies from almost the beginning. Is a man a man or is he a samurai, a yakuza, a soldier, or even a lover who must suppress his feelings and kill his friend, his wife, his lover, or even himself because that is what is expected of him? What must a woman do simply because her children, her family, or her social position demand it of her? American movie heroes are individuals who tend to resist social integration, who hold to their own rules and make their own way – the Western hero riding out of town is the epitome but he can be found still in the cop who refuses to go by the book but still gets the bad guys, Thelma and Louise driving off the cliff, or simply the kid who leaves home or more recently the woman who gets a divorce in order to make her own life – and the isolation of modern urban life is often self-imposed. Japan, at least as we have seen in the movies, has been a society in which the individual is submerged into the family, the village, the clan, where ronin will do anything to find a new daimyo or young men will join the yakuza to find someone to give them a set of rules to follow and a caste to which to belong. As we have seen even in war movies, decisions were built on consensus, all of which demands a suppression of individual desires. Cure taps into the idea that such suppression nurses a resentment that if ever released would lead to terrible violence in a social order that sees very little violence on a daily basis. As Takabe’s friend says, hypnosis can’t make you do something you wouldn’t normally do; the hypnosis depicted here frees the subjects to do that which they have always wanted to do but have never admitted, even to themselves.

Cure was the movie that made Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s reputation and in effect changed the course of modern J-horror, preceding Ringu in Japan though Ringu was released before it in the international market. While the traditional revenge of a spirit, often a wronged woman, would continue to be a regular part of Japanese horror movies (see the Ju-on franchise, for example), Cure and others in its vein had no individual villain, avenger, or ghost haunting the protagonists. Rather, the horror was something that had simply gone wrong, something in the air, something in the zeitgeist, just some indefinable Something that released death into an otherwise stable, normal world.*

As a film-maker, Kurosawa is firmly in the Mizoguchi tradition of Japanese film-making, rather than that of the other (unrelated) Kurosawa, yet without the appearance of interest in beautiful compositions. Most of the scenes are in long takes, often with characters in middle distance. It is a visual world similar to Sting of Death, another movie dealing with a wife’s mental illness, or Kurosawa’s own earlier Guard from Underground, all browns and grays and bland generalized lighting indoors. When forced outdoors, we find only overcast beaches and muted exteriors, so there is no relief from the blandness which itself becomes a part of the menace. All the interior rooms are too large, which further emphasizes the isolation of the characters and the emptiness of their current situation. That care and consistency, when joined by two striking performances from Koji Yakusho as Takabe and Masato Hagiwara as Mamiya, makes it far more than a detective movie or a horror movie.

* This feeling may well have been stimulated by more than the increasing isolation of an urbanized Japan; in 1994-95 the Aum Shinrikyo cult had released deadly sarin gases on several occasions, culminating in the Tokyo subway attack of 1995, which brought a general sense of unease to the urban populations throughout the nation.

.

Pingback: License to Live / Ningen gokaku (1998) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Suicide Club / Suicide Circle / Jisatsu sakuru (2001) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Charisma / Karisuma (1999) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Ghost in the Shell / Kokaku kidotai (1995) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Raigyo (1997) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Another Heaven / Anuzahevun (2001) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Pulse* / Kairo (2001) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Monday / Mandei (2000) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Doppelganger / Dopperugenga (2003) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Bright Future /Akarui mirai (2001) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Retribution / (2006) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Inugami (2001) | Japanonfilm