In Kaneto Shindo’s Hokusai manga, we are given a ribald and vigorous look at the life of the famous artist generally known as Hokusai. Along the way, we get some lively recreations of the inspirations for some of his most famous works while we eventually reach an examination of the loss of artistic powers in old age and an unexpected critique of the Japanese emotional reserve.

In Kaneto Shindo’s Hokusai manga, we are given a ribald and vigorous look at the life of the famous artist generally known as Hokusai. Along the way, we get some lively recreations of the inspirations for some of his most famous works while we eventually reach an examination of the loss of artistic powers in old age and an unexpected critique of the Japanese emotional reserve.

Hokusai is portrayed as the rather typical starving artist of western movies. He even lives in a garret, a small room over a sandal maker’s shop because the landlady never quite gets around to throwing him out for late rent, staying alive with the occasional handout from his father, who has disowned him for becoming an artist. His inspiration comes to him, as he says, like a rain storm, and we first see him walking and running through the rain while everyone else takes shelter.

Though he has had many wives and mistresses, so many he can’t remember them all, one of the earliest left him a daughter who lives with him now. He is overwhelmed by a chance meeting with Onao, one of the strangest and most enigmatic characters we’re likely to find anywhere. She says almost nothing, but responds to comments only with a funny sound made with a leaf on the tip of her tongue. She will drop her kimono almost without invitation yet not actually sleep with the men she drops it for. Hokusai sends her to his father, who is so overwhelmed and confused by her that he commits suicide after she disappears. Hokusai himself embarks on a series of pornographic images drawn from his memory of her, though he never had sex with her himself.

She will drop her kimono almost without invitation yet not actually sleep with the men she drops it for. Hokusai sends her to his father, who is so overwhelmed and confused by her that he commits suicide after she disappears. Hokusai himself embarks on a series of pornographic images drawn from his memory of her, though he never had sex with her himself.

In another rainstorm of inspiration, he takes off for a trip around Mt. Fuji, leading to the famous “34 Images of Mt Fuji” and the “Great Wave,” while we shift our attention to Bakin, husband of the nagging landlady. One of the great writers of the period, though not very well known outside Japan, he is here seen as a hen-pecked husband who can only write when sneaking off to the toilet. Eventually, his wife dies, leaving him the shop to sell and enabling him to live off the proceeds while he writes.

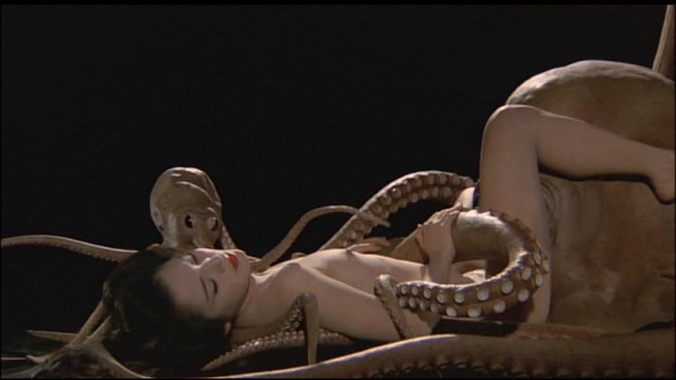

Our final section shows Hokusai at 90, famous but living again in a shack and borrowing money from a blind Bakin, planning the masterpieces of the next 10 years once he learns perspective from western artists. His faithful daughter Oei has found a young girl who looks like Onao, which inspires one last masterpiece (the woman and the squids which had historically been painted thirty years earlier) before he dies.

Despite having Ken Ogata as Hokusai, the movie is really held together by Yuko Tanaka as Oei.

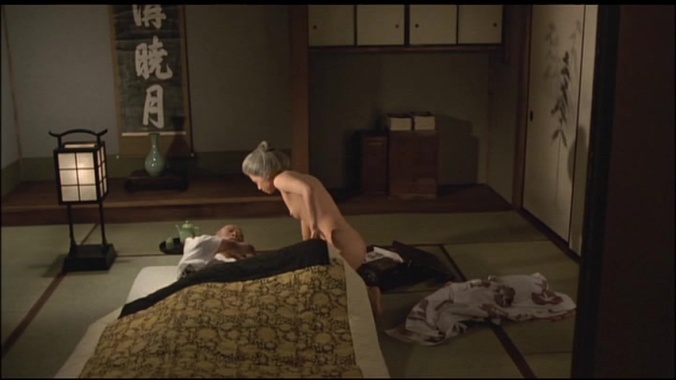

First seen in her teens sleeping topless, she is her father’s keeper, making sure he is fed and comes in out of the rain and knowingly keeping him sane during the strange relationship with Onao. More than willing to talk back to her father, she becomes Hokusai’s (and Shindo’s) perfect wife in all but sexual relations: She finds publishers for him, on occasion models nude for him, emcees his great stunt of the gigantic portrait of Daruma and a painting on a grain of rice, waits for him while he wanders the country for his Mt. Fuji views, and tends him in his old age. She herself has never married, for she has always been in love with Biken, who never noticed. At last, when widowed, Biken asks for her help and she begins to quietly undress, only to realize that he dictates his stories while lying in bed and he only wants a good secretary. Finally, however, as the old blind Biken (Toshiyuki Nishida) is dying, she undresses to keep him warm under the cover and in his final moments to offer her breast to suckle.

As a quick look at Wikipedia or any Japanese art history will indicate, Hokusai manga plays fast and loose with the historical record, but then it is not about the real Hokusai, any more than the dozens of movies about Musashi Miyamoto are about the historical swordsman rather than the myth. It is about the role of and the mysterious mental workings of the true artist. That it falls into some of the traditional clichés of western depictions of artists like Van Gogh or the fictional Gully Jimson, for whom art is a kind of madness, simply indicates that what separates Hokusai and his contemporary Utamaro from the hundreds of other Japanese printmakers of the day is inexplicable.

It is also a commentary on the society’s repression of real feelings. Utamaro’s days of house arrest indicate the political suppression of the time, but Hokusai’s art often has to be sold “under the counter,” so to speak, rather than circulated as regular prints because of its earthy subject matter. The Japanese, as we have seen in many other movies, have a long tradition of the “farewell poem,” something similar to the western last words, but thoughtfully composed by the dying person rather than taken down at the moment of death or remembered later by witnesses. In an early scene in a bathhouse, we see other writers and artists who have composed farewell poems for their old names as they adopt new ones. Some are beautiful, others more down to earth, like “Life is like a fart, there and then fading away.” And we end the movie with Hokusai’s own farewell poem. But before that, he finally thanks Oei for all she has done for him. Similarly, Biken’s much older wife (Nobuko Otowa) on her deathbed contradicts all her previous nagging and spying to say he has been all the husband she could ever have wanted. Why, Oei asks herself, do they say nice things only when they are dying?

Produced by Shochiku rather than by Shindo’s independent company, the movie has an actual budget, which allows for color and for crowds that he could rarely afford in his independently produced films. There is also money for special effects, the most spectacular of which is the scene in which the second Onao acts outs the “Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife” and is caressed, kissed, and given cunnilingus by two large squids (If puppeteers were credited, they are not translated in the subs). The movie is rich in activity, so much so that only in the final scenes do we begin to suspect it was based on a stage play. It also has something we have not seen from Shindo before – good-natured humor.**

The movie is rich in activity, so much so that only in the final scenes do we begin to suspect it was based on a stage play. It also has something we have not seen from Shindo before – good-natured humor.**

Only the old-age scenes seem false, with not much help given to the actors by the makeup department. Then again, no matter how much you age the face of Tanaka, the moment she strips off to join Biken’s deathbed, she still has the body of a 25-year-old. In other scenes, however, she actually seems to do better with the portrayal of aging than do Ogata or Nishida.

At this date, Shindo was nearing 70, an age when the creative artist begins to think that every project might be the last. We know he would continue to make movies until he was almost 100, but he could not have known that. It’s hard not to see him projecting onto Hokusai that dream of all the great works he would make in the future, while at the same time pausing to produce an earthy and fascinating great work right now, while the chance is still available. All of his remaining ten movies are even harder to find than his movies of the seventies, so I can not yet say from my own experience if there was a decline or a change of direction in later years. Still, it is a real shame that Hokusai manga remains all but unknown today.

* The Japanese title refers not to a comic strip but to the fifteen volume Hokusai manga that broke new ground with thousands of pictures of items and activities of everyday life, one of the most fundamental visual sources for Japanese historical research but also a tremendous influence on the Japanese idea of artistic value to be found in the little things of everyday life.

** No copies of Operation Negligée (1968) have managed to reach DVD anywhere that I can find, so I can’t judge how effective the comedy in that movie may have been.

Pingback: Legend of the Eight Samurai / Satomi hakkenden (1983) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Amagi Pass / Amagi goe (1983) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Wuthering Heights / Arashi ga oka (1988) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Strange Tale of Oyuki / Bokuto kitan (1992) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Moonlight Serenade / Setouchi munraito serenade (1997) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Sharaku (1995) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Swallowtail Butterfly / Yentown / Suwaroteiru (1996) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Will to Live / Ikitai (1999) | Japanonfilm