Hitokiri is a magnificent historical epic set in the 1860s and anchored by a character study featuring Shintaro Katsu in one of his finest, most complex roles, Tatsuya Nakadai as his devious master, and plenty of swordfights, blood, visual imagination, and even a strange kind of love story. However, this can be a very confusing period, especially to non-Japanese viewers, so you may wish to look at the very brief summary in the long footnote below.

Hitokiri is a magnificent historical epic set in the 1860s and anchored by a character study featuring Shintaro Katsu in one of his finest, most complex roles, Tatsuya Nakadai as his devious master, and plenty of swordfights, blood, visual imagination, and even a strange kind of love story. However, this can be a very confusing period, especially to non-Japanese viewers, so you may wish to look at the very brief summary in the long footnote below.

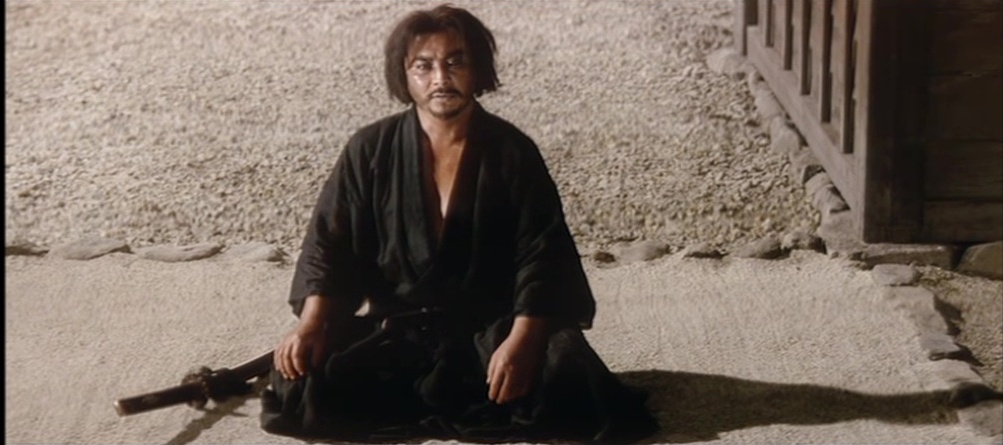

Katsu plays Izo Okada, a lonely and poor samurai in the small and poor Tosa clan. Unable even to sell his armor, which falls apart when touched, he falls under the spell of Hanpeita (Tatsuya Nakadai), who sends Okada to observe three men sent to assassinate a samurai called Yoshida. This does not go well, in the sense that it is much more realistic than the usual chanbara fight in the moonlight, and it takes a long time for Yoshida to finally die. Okada is inspired by the slogan they use – tenchu, meaning heaven’s punishment – and by his belief that he could be a far better killer, which turns out to be true.

Soon afterward, we shift to Kyoto, where Hanpeita and his men have gone, and the narrator provides a long list of Okada’s murders. Okada, however, does not seem to have changed much. He is still the crude, vulgar, and dirty fellow he was at the beginning (which is not the way the history/legend describe him). Had we not seen the armor, we might think he was a peasant trying to become a samurai. He is not all that bright and is in such awe of Hanpeita that he is content to do anything he is told without question and to live on the pittance he receives after each kill. Even the prostitute he regularly visits berates him for his stupidity, since they only pay him enough to afford her rather than a real geisha like the the other samurai hire. He keeps crossing paths with Ryoma Sakamoto (Yujiro Ishihara), who warns Okada that a master will often turn on the most faithful dog when a mistake is made, but his trust in Hanpeita is complete. After he rushes to aid in an assassination that he was not ordered to participate in, Hanpeita refuses to pay him. Unable to find work with other clans, he returns in even more abject submission. One morning, he is rousted from his stupor in the whore’s room by the “Ronin Patrol” and obstinately refuses to give his name, so they arrest him. Fearing a political trap, Hanpeita refuses to identify him to get his release, so he serves 18 months in jail for vagrancy, after which he is sent home. His only friend from the old days appears with some poisoned sake; the friend dies drinking the sake to prove it is safe, but Okada survives, only to be questioned by a commission about the Yoshida murder years earlier. He promises to reveal the true killers, if money is sent to pay off the prostitute’s debts, and then spontaneously confesses to all his other murders, leading to his own execution.

Hideo Gosha made so many fine movies that we can hesitate to call this his masterpiece, but the film’s anchor in not just a set of historical incidents but also the complex and unusual character of Okada gives it a greater emotional depth than many of Gosha’s other superb genre films. In addition, it demonstrates a marvelous control of the camera. Like Goyokin made the same year with a different photographer, it is a color film full of shadows, as beautifully framed and controlled as in the finest black and white films of the era.

There are excellent performances by Nakadai which by this date we almost take for granted and by Mitsuko Baisho as the prostitute, but it is Katsu who must hold the movie together.

Mitsuko Baisho

He combines the physicality and crudity that had emerged as early as Killer Whale with the more open emotional intensity of Devil’s Temple, while still making clear his desperate need for someone he can trust and his earth-shattering collapse when that trust is finally betrayed. Though distributed by Daiei, the movie was produced by Katsu’s own company, indicating that he seriously wanted to play the role, perhaps even over the studio’s objection. By 1969, Katsu’s relationship with Daiei was ending. He set up his own production company in 1967, which produced Tenchu, his last movie distributed by Daiei; his Daiei Hoodlum Soldier and Bad Reputation series both came to an end and all later Zatoichis were distributed by Toho. Though we have no clear evidence explaining this break-up, it is clear from his own productions that he was trying to expand his series personae, first with the art-house detective movie Man Without a Map and then Tenchu, while all his later Zatoichis were much darker and more nihilistic in tone.

Gosha has long been a cult figure for action movie fans, but Hitokiri and Goyokin, made back to back, are among the finest movies made in Japan, whatever their genre.

* During the years after the foreigners appeared in Tokyo Bay, Japanese politics threw up an enormous number of revolutionary plots. By 1861-62, the most visible of these was the sonno-joi (revere the emperor, expel the barbarians) that sought to overthrow the Shogunate and restore the Emperor to authority. That movement in itself took many forms, but initially was masterminded by Hanpeita Takechi of the relatively small and poor Tosa clan. He worked primarily through a set of four assassins, the hitokiri, including Izo Okada, the subject of this movie, who murdered at least seven men (though the list in the movie is longer) and Shinbei Tanaka. The threat of these assassins led to the Shogun’s organization of the group that eventually became the Shinsengumi to act as his own protection when he visited Kyoto to consult with the Emperor personally and marry the Emperor’s sister, and the Shinsengumi became the most powerful force in Kyoto, until the combination of their own infighting, over-reach, and opposition from the Satsuma and Chosu clans led to their destruction. In 1864, another poor northern clan tried to organize a rebellion along the same lines as the sonno-joi, which eventually became the tengu-to and was again destroyed by its own infighting. Shortly afterward, the various plots erupted into open warfare, during which the Shogun was defeated. Thus, if you are trying to deal with history through sixties movies, Hitokiri mostly lies between Samurai Assassin and Ansatsu, with the various Shinsengumi movies following, then Tengo-tu and continuing into the Boshin War touched on in Red Lion that defeated the Shogun completely. Movies being movies, their accuracy in detail is not necessarily trustworthy, but in general shape, they provide a good insight into the 1860s, at least as seen through the eyes of the 1960s.

Hitokiri (aka Tenchu) is one of the greatest films to come out of Japan, and with it some controversy and a lot of historical significance. The Tosa domain situated on the island of Shikoku was ruled by a “Tozama” (or Outside) daimyo named Toyoshige Yamauchi (better known as “Lord Yodo”). Tozama daimyo were lords that became hereditary vassals of the Tokugawa after the Battle of Sekigahara. The victim of the assassination that Izo Okada watched was Toyo Yoshida, who had been appointed to reform and modernize the domain. The rebellious element led by Hanpeita Takechi was opposed to Yoshida’s reforms and much like the Sakurada Gate Incident took action against a progressive leader.

As with many samurai films, most, if not all the characters are based on real historical figures, and interestingly while Izo Okada is portrayed as an unkempt ruffian, Ryoma Sakamoto is well dressed and respectable looking. History paints a different portrait of Sakamoto, but commentary on that is probably best saved for another movie, perhaps one about him like “The Ambitious” (Bakumatsu) produced by and starring Kinnosuke Nakamura.

The controversy comes into play with famed author Yukio Mishima who played Satsuma clan swordsman Shinbei Tanaka. In November of 1970 Mishima committed hara kiri in public view as a protest against the loss of samurai spirit in modern day Japan. A skilled swordsman in real life Mishima’s fight scenes were brutally violent against the actors he faced in the film. Still to this day the accusation that he assassinated

a high ranking noble Kintomo Anegakoji is unproven, although his sword was found at the scene.

Produced by Katsu Productions and Fuji Television, the film was originally distributed by Daiei, but didn’t reach Hawaii until after Mishima’s death where it played at the Toho Theatre. All four major studios had a theater in Honolulu, the aforementioned Toho, Shochiku had the Nippon Theatre, Toei had the Toyo Theatre, and Daiei had the New Kokusai Theatre which showed all the Zato Ichi movies up until “The Blind Swordsman Meets His Equal” (aka Zato Ichi & The One-Armed Swordsman). Before Toho started distributing the works of Katsu Productions this movie and the previous “Zato Ichi’s Fire Festival” were distributed by Dainichi-Eihai as Daiei was falling into bankruptcy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. The background on Yoshida helps clarify a lot. I didn’t mention Mishima’s role, essentially little more than a cameo, because I didn’t want to get into the Mishima seppuku that happened shortly after and otherwise distract from the movie. It’s always interesting to hear from someone who can remember many of these movies when they were new.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Shinsengumi: Assassins of Honor / Shinsengumi (1969) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Portrait of Hell / Jigukohen (1969) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Zatoichi Goes to the Fire Festival / Zatoichi abare-himatsuri (1970) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Wolves / Prison Release Celebration / Shussho iwai (1971) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Last Samurai / Okami yo rakujitsu o kire (1974) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Tatsuya Nakadai | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Flames of Blood / Hono-o no gotoku (1981) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Geisha / Yokiro (1983) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Four Days of Snow and Blood / 2.26 (1989) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: World Apartment Horror (1991) | Japanonfilm

Thanks for this reliably trenchant and illuminating analysis/appreciation. Was utterly unprepared for how great this movie was. One Q/quibble, however. Re. “Unable even to sell his armor, which falls apart when touched,” Am I wrong in thinking that he found the armor in question, long abandoned in the decrepit building he’s searching for food in the beginning, rather than the armor being actually his? I may have misunderstood your copy or the film (or both!) mind you, but it seemed clear to me (and, I thought, added an interesting additional layer to an admirably layered, mostly dialogue-less intro) that the armor belonged to some likely long dead samurai.

LikeLike

I thought it was his in storage for so long that he had to dig it out, but it is possible that it was someone else’s. In either case, it means he no longer had any of his own.

LikeLike

Gotcha. Need to rewatch it. My flawed interpretation had him basically overnighting in an abandoned temple or dojo or private home and discovering the armor. It WAS a lot of dust he blew off… Gave it a sort of Narnian golden age passed by kind of mythic feeling but i was probably projecting…

LikeLike

Whether or not the armor was from his family is of little import. The opening is just to show how poverty stricken Izo was. What he says in the meeting with Takechi spells out his dilemma in no uncertain terms. Tosa samurai were of different caste levels. Izo, like Ryoma Sakamoto, were of the lowest class of samurai, scorned by the upper echelon.

LikeLike

Pingback: Yakuza Masterpiece / Ode to Yakuza/ Fine Yakuza Song/ Yakuza zessho (1970) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Taboo / Gohatto (1999) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Izo (2004) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: One Thousandth Post | Japanonfilm