Beginning in 1945 and then continuing through the Occupation years, The Lady of Musashino gives us a view of the end of the old Samurai class reflected not through the soldiers and landlords but rather through the woman’s melodrama plot.

Beginning in 1945 and then continuing through the Occupation years, The Lady of Musashino gives us a view of the end of the old Samurai class reflected not through the soldiers and landlords but rather through the woman’s melodrama plot.

As the bombs begin falling on Tokyo, Kinuyo Tanaka and her professor husband Masayuki Mori are forced to move back in with his parents on their family estate in the countryside outside the city. As often with Mori’s characters in this period, he is a weak, would-be philanderer but Tanaka puts up with it because that is what traditional wives do. Understanding his son all too well, Mori’s father wills the estate to Tanaka rather than his son.

The neighbor is a munitions manufacturer who got rich in the war and somehow manages to hold onto the wealth during the Occupation, but he has a wife with a wandering eye who eventually takes up with Mori. Meanwhile, a young cousin finally is repatriated from his POW camp and comes to the estate. Tanaka falls madly in love with him (or at least as madly as Mizoguchi ever allows his women to fall), but nothing comes from this. He spends much of his time away from the estate drinking and chasing women, much like his uncle, while she holds to her faithfulness to her husband. Eventually, the rebuilding and expanding Tokyo begins to encroach on the estate, Mori wants to sell the estate to have money to run off with the neighbor woman, and Tanaka commits suicide.

Interestingly, Tanaka takes cyanide which she had kept since 1945, when the government issued it to residents in case the invasion came. I haven’t seen this mentioned in other movies, and it is hard to believe the entire nation was awash in cyanide after the war, so perhaps this was only issued to the upper class who were expected to uphold the traditions of suicide when the end came.

Without any real knowledge of Japanese property law, I really did not understand how, if the estate had been willed to Tanaka, Mori could still sell it off, nor did I understand how her death would somehow prevent that happening after she was gone. Perhaps through a misreading of the subtitles I misunderstood what was intended to be an act of complete self-sacrifice, removing herself from her husband’s way since everything she had held dear from the past was disappearing. Certainly, her suicide note indicates her sadness at the end of Old Japan.

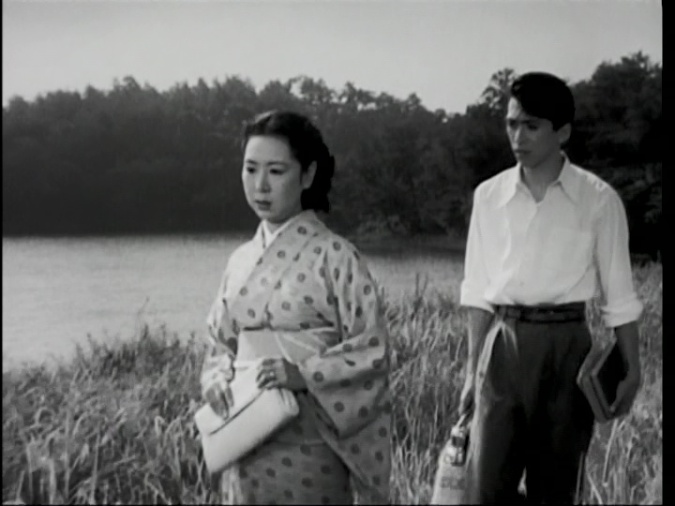

However you read the suicide, it is a Mizoguchi movie, which means that some of the scenes are visually superb. Remarkably, he spends rather a lot of time outside the studio, from the shots of Tanaka and Mori fleeing the faraway bombing to long walks along the lake with Tanaka and the young man. Mizoguchi was one of the most intensely studio-bound directors of the age, for only there was he was in complete control. Here he is often outside and not just on the backlot. His photographer was not a regular; this time it is Masao Tamai, who would not work with Mizoguchi again but would later photograph many of Naruse’s most famous movies.

This seems to be the first movie in which Mizoguchi used a crane, so there are some unusually high angles and a number of shots in which the camera goes over the top of the family’s wall and then ducks under their trees as people walk through the gate.

Tanaka tormented by her suppressed love

Otherwise, there are a lot of dolly shots as you would expect, though usually accompanying people on walks.

As in Madame Yuki, which was made immediately before this film, the contrast between the elegant old Japan and the modern is pretty heavy handed. The neighbor woman often dresses in the gaudily modern way,

Wife and mistress, Old and New Japan.

and the young cousin’s friends are all essentially “sluts,” not prostitutes but rather “modern girls” in modern clothes who party and sleep around. We don’t see sex scenes, of course, but there is no attempt to gloss over the sexual aspect of their relationships, and we see at least one very clear “morning after” scene, though she is fully dressed by the time the camera finds her.

Tanaka and Mori are both up to their usual high standard. I found it a bit difficult to take Akihiko Katayama seriously as the cousin/heartthrob, since he often reminded me of Alvin the Chipmunk when he spoke, but others have not found that distracting.

Also like Madame Yuki, this is one of Mizoguchi’s least known films outside Japan, but the pair of them form the clearest depiction of the fear held by so many Japanese after the war that their society would not just be reformed but destroyed, not necessarily by the Americans but by the Japanese themselves.

I remember cyanide being mentioned in another Japanese movie, Okamoto’s 1967 film ‘Japan’s Longest Day’ where a vial of potassium cyanide is shown being given to a military officer. A civilian having government-issued cyanide pills is historically accurate, and is part of one of the most tragic and shameful events of Japanese history. There was more access to cyanide in Japan than in Nazi Germany, with civilians having it in their reach more than anywhere else in the world, and yet, in spite of this, there are reasons why it is hardly ever mentioned. One is because traditional Japanese culture, like many other cultures, has a tendency to remain silent when something is deemed unacceptable or embarrassing.

In reality there were no “traditions” of suicide in any class of Japanese civilian culture at the time, nor had there ever been, and certainly not in that context. Japan had never been successfully invaded before nor had they ever had to surrender militarily to a foreign power so there was no precedent. (But even in their civil wars the defeated population was not expected to die.) Ritual suicide (harakiri or seppuku) was actually a form of capital punishment for a crime, but in ancient Japan the samurai class were permitted to perform their execution themselves, and their wife was expected to do the same. (Anyone who wasn’t of that class who committed that same crime would be executed by someone else.) Then their properties would be confiscated by the state. There was no honor in it, it was a disgrace and shame to a family, who would be left without a place to live. It was romanticized and glorified by legends, poets and authors in the 19th century after it was outlawed. But less than 15% of Japan had been samurai, so it was never something the majority of the culture could relate to. (There’s an excellent documentary that was directed by Tony Long titled ‘The Samurai’ that explains part of this in detail.) And then in the 20th century the Japanese military further corrupted their history by teaching their troops about death and suicide “traditions” that had little or no basis in actual Japanese history. Unfortunately many of these misconceptions persist to this day.

In reality, this film accurately portrayed what happened to most of the cyanide the government issued. Which was nothing. The family had never used it. Several years after the surrender and the family was still alive. Hardly newsworthy, which is yet another reason why it has been largely forgotten.

But that brings us to the dreaded question of why cyanide was issued in the first place. In early 1945 the Japanese government agreed on a bizarre policy and officially expected the entire civilian Japanese population to sacrifice itself and die, thus the saying: “The shattering of the hundred million like a beautiful jewel.” So they began issuing cyanide to civilians. (Though they did not have enough for the entire population, they did supply incredible amounts to certain districts.) So yes, though it may be difficult to grasp, parts of Japan were awash in cyanide prior to the surrender. And being frugal, a typical Japanese household would not throw anything away.

Most of the world, including modern Japan, does not fully understand the various cultural and wartime influences that shaped the mindsets of that era. It isn’t impossible to understand, but it requires more study and time than most are interested or willing to commit to, so more often than not the context of suicide in WWII Japan has been completely misunderstood. Surprising as it may seem, most WWII-era Japanese were not suicidal. But if you’re told that you’re going to be tortured to death, or that the invading troops will actually eat you alive, and facing what they thought was certain death either way, suicide may seem the lesser of the two evils, thus part of the cause of the deaths of 1/3 of Okinawan civilians. Then there’s the propaganda from some in the American military that led to needless murders: they were told that all Japanese were lunatics and suicidal anyhow so many civilians and prisoners were killed — with both sides fueling the others’ propaganda. The lies are so far-fetched from reality that today it seems almost unbelievable, but the Japanese-are-naturally-suicidal myth persists to this day. We seem to have forgotten that American women were taught to “save the last bullet” during the Indian Wars, and were expected to commit suicide rather than be taken alive by Native American Indians — this was a common practice west of the Mississippi. Without understanding the context of that practice, without the knowledge of what those women faced, one could misinterpret history by saying that 19th century America was a society that accepted and demanded suicide. One has to delve into the context before making generalizations.

The only two films I have seen that address the question of the mass suicide of the entire Japanese population are the aforementioned Okamoto film and Kosaku Yamashita’s 1974 film ‘Father of the Kamikaze’.

In yet another indirect cultural/political message, Naruse’s 1966 film ‘Hikinige’ mentions potassium cyanide as the cause of Yoko Tsukasa’s character’s suicide, but most modern viewers would not realize that that was a reference to the government-issued cyanide pills of WWII. You couldn’t buy it at a pharmacy, she had it at home, courtesy of a deranged WWII-era government policy.

LikeLike

Thanks again for another thoughtful and detailed comment. I would suspect that many a wife and daughter on a southern plantation or farm was also taught to save the last bullet for themselves when the slave uprising came, but I can’t recall if that made it into “Gone With the Wind.” I missed the allusion in “Hikinige.” But there is also the question of movies versus historical fact, and there are certainly a lot of Japanese movies in which samurai commit harakiri without having committed a crime — “Harakiri” for an obvious start, or the opening of “13 Assassins.” We’re probably in the same kind of territory we would be with American Westerns — the real West had very few “draw podner” events, but the Western would not exist without them. Similarly, suicide, both the harakiri and the love-suicide, probably shows up in Japanese movies far often than it ever occurred in real life. I haven’t yet seen “Father of the Kamikaze,” but I have seen “The Human Bullet” and “Dr. Akagi,” in which the attitude is more along the lines of “We shall fight them on the beaches,” with the recruit and his single grenade or the women drilling with their sharpened bamboo spears. And there is certainly no doubt that the younger officers in “Japan’s Longest Day” are living on some other planet than the real Japan around them. Thanks again.

LikeLike

On another note, I saw Tanaka’s character as having traditional views of honor, and her character’s suicide as a senseless form of escape. Escape from the shame of being abandoned by her husband, escape from the temptation to be unfaithful, and ultimately escape from the torment that the man she loved did not love her. In the old days her husband would’ve been less likely to abandon her — or so she thinks — and more likely to remain near his father. The fact that the father is trying to provide for his daughter-in-law directly is already an indication that the father has given up on his son and doesn’t trust that his son will take care of his daughter-in-law and that she will essentially be left with no place to live were her father-in-law to die. (In 19th and early 20th century Japan, a man could divorce his wife rather easily, just by writing up a letter of divorce stating the reasons and the date and it would go into effect immediately. She would then be sent back to live with her family. But if she had no family, Japanese law required that her ex-husband or his family provide for her and shelter and feed her for the rest of her life. That protective law no longer existed but has influenced Japanese culture greatly. She had a traditional father-in-law who wanted to take care of her and was making preparations.) He also understood his son would probably squander the estate. By ensuring his honest daughter-in-law would inherit the property, then other relatives could continue the tradition after her generation had gone. If her father-in-law had already transferred everything to Tanaka’s name, then legally her husband “inherited” it upon her death. Either way, even had her father-in-law done nothing, the son would eventually inherit the estate anyway so I didn’t think that the property factored into her suicide reasons. The Occupational government changed the divorce laws so that women were given a direct right to initiate a divorce (indirect right through a brother or father already existed but was rarely used), but she being traditional that might be considered a dishonorable and disloyal thing to do to her husband, if she was even aware of it to begin with. Divorce would possibly have left her homeless depending on her father-in-law’s reaction to it, but would’ve been a far better solution than throwing her life away.

(I’m not advocating divorce, but it is preferable to suicide which is such a needless waste of life. Postwar Japanese women at the time might not have realized it, but legally they were the most “liberated” in the world. The Occupation forces, in trying to dismantle what they considered feudal, had inadvertently given Japanese women some form of equality to men with regards to divorce laws that were already quite advanced. Once American women started to get wise to this, they wanted similar divorce freedoms but it would be decades before American women would have access to even part of those “freedoms”. Some of the American men in charge of Japan regretted this, but it was too late and to “save face” left the divorce laws in Japan alone — it would’ve looked pretty silly to change them back again.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

My reading from the subtitles I saw with the film implied the following:

1) The land had belonged to Michiko’s parents, not her husband’s (it is her parents we meet at the beginning, who then pass away). So her father left the lands directly to his daughter rather than to his son-in-law, as apparently would have been customary.

2) Michiko’s husband, despite not owning the land, had power of attorney over it (presumably by virtue simply of being the husband), and thus had the power to sell the land on his wife’s behalf without her expressed consent. Michiko learns that he intends to do this, and abscond with the money from the sale (which should rightfully be given to her).

3) The idea behind her suicide is that if she dies before her husband has sold the land, and leaves a will bequeathing the land (or at least the two-thirds she is allowed to distribute) to her cousin, her husband will no longer be able to sell it, and the land will remain in her father’s family (the cousin is the son of her father’s brother).

This is what she does, although the cousin storms off angrily at the end, saying he doesn’t want the land and telling Michiko’s husband he can keep it.

The audience sees (as Michiko does not) that Michiko’s husband was having trouble selling the land, with prospective buyers seemingly uneasy about purchasing it without a note of consent from Michiko, so her suicide (even according to the flawed logic behind it) was likely not the only solution to the financial issue.

LikeLike

That certainly helps to make some sense of the property issue. Thanks. Yet another illustration of how mis-reading or mis-titling can affect the way we understand something that would have been obvious to the original audience.

LikeLike

Pingback: Ugetsu monogatari (1953) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Dancer/ Dancing Girl /Maihime (1951) | Japanonfilm