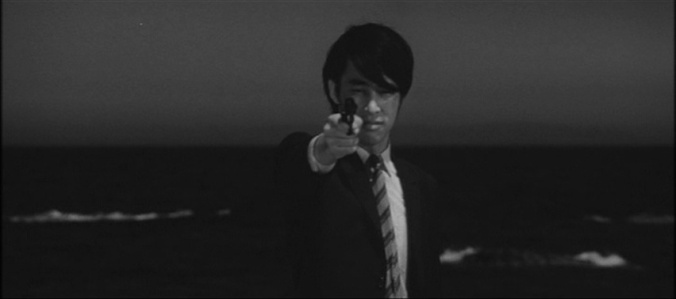

Based on a real-life case, Kaneto Shindo’s Live Today, Die Tomorrow provides a complex and yet frustrating examination of disaffected youth. Michio graduates from “middle school” and along with all the boys of his class is shipped on a government work program from Hokkaido where there are no jobs to Tokyo. He ends up working for a specialty fruit seller, with restaurants and other related businesses. After a while, he leaves that and finds other various jobs, none of which he stays at for very long. Eventually, he applies for the Self-Defense Force but is turned down; on his way out of the base he goes into the US housing and takes a pistol from a woman’s purse. He shoots a security guard at a swimming pool, then later another one who wakes him while he is sleeping rough. For no particular reason, he kills a couple of cab drivers. He meets and settles in with a young prostitute and gets a job as a waiter. The girl goes back to her old lover. Eventually he ends up sharing his room with two bar hostesses who rob their customers by drugging their drinks, until they are beaten up by a yakuza for working without permission in his territory. Michio eventually shoots him, then is later arrested and taken to jail.

Based on a real-life case, Kaneto Shindo’s Live Today, Die Tomorrow provides a complex and yet frustrating examination of disaffected youth. Michio graduates from “middle school” and along with all the boys of his class is shipped on a government work program from Hokkaido where there are no jobs to Tokyo. He ends up working for a specialty fruit seller, with restaurants and other related businesses. After a while, he leaves that and finds other various jobs, none of which he stays at for very long. Eventually, he applies for the Self-Defense Force but is turned down; on his way out of the base he goes into the US housing and takes a pistol from a woman’s purse. He shoots a security guard at a swimming pool, then later another one who wakes him while he is sleeping rough. For no particular reason, he kills a couple of cab drivers. He meets and settles in with a young prostitute and gets a job as a waiter. The girl goes back to her old lover. Eventually he ends up sharing his room with two bar hostesses who rob their customers by drugging their drinks, until they are beaten up by a yakuza for working without permission in his territory. Michio eventually shoots him, then is later arrested and taken to jail.

Shindo tells the story in a complex fashion, so the time sequence is not always clear. The first scene shows Michio finding the gun then without warning we are back at a marathon race he won and a teacher bringing him to Tokyo. After the first shooting, we take another flashback to his mother’s life, detailing how, with seven children and a missing husband, she eventually leaves Michio behind with two teenaged sisters while she goes off to find work elsewhere. His two older sisters die trying to keep him and a brother alive. Then we are back to the present, with the bar girls and prostitutes. At least, I think that’s the structure. The only real clue we have to various time shifts is Michio’s suit, bought on credit after his first paycheck. But the “present” seems to cover about three years.

Unlike Kinoshita’s disaffected poor young man with the rose tattoo, Michio is not a child of the war years and he shows anger only twice, when he is turned down by the Self Defense Force and when his mother comes to visit him in prison. Otherwise, he is inexpressive, even with the young women. Aside from the shooting of the yakuza, his killings have no plan, no purpose, no connective tissue other than a spontaneous response to the situation. In America, we would see such a portrayal as a strong argument for gun control, because the only reason he kills people is that he happens to have found a gun. Without that, he might have gotten in fights, but no one would have been killed. He would have just continued to live randomly until some job held him long enough for him to find a wife.

He eventually writes down a promise to live now and die when he is twenty, but he neither enjoys the high life of a young man trying to live to the max nor makes any attempt at suicide as twenty approaches. The title and his wish probably refers to Japan’s laws which treated criminals as children until they were twenty.*

As the mother, Nobuko Otowa is convincing at all her ages. She is a child of poverty who makes the mistake of falling in love with a handsome but shiftless man. He disappears for long periods, but when he returns she can’t resist him, resulting in seven children she must care for by herself. She even takes in one of her husbands bastards from another woman. Still, there is nothing for her to do on Hokkaido, so she goes to the main island to find work, taking only the youngest baby plus her eldest daughter and the half-sister.

This is a remarkably dispassionate movie for Shindo. In his earlier movies, he could be almost documentary-like (see Naked Island or The Wolves), but it was always clear where his sympathies lay. Michio, though his subject, does not seem to be a figure Shindo can or will explain. The movie could be an indictment of the situation of the poor left behind, but Michio is part of a program intended to help bring the poor of his generation into the mainstream of new prosperity. He is not mistreated or underpaid in his various Tokyo jobs – he just tires of them and moves on, always with the promise, never fulfilled, that he will go to night school to get his high school diploma. He feels his mother deserted him, but she really had no other choice at the time. None of his shootings, except the yakuza, are motivated in any visible way; the people he kills have not harmed him or endangered him. But neither is he on a killing spree for fun. He seems to be a unique and isolated case, but when one of his classmates is interviewed after his arrest, the classmate casually says, “I wish I had a gun,” then after realizing what he has said adds, “Just joking.”

How much of the movie follows the facts of the original case I can’t say, but it is interesting that, even at this early date, it is simply taken for granted that any American would have a gun, even a civilian woman living on a military base in Japan, about as safe a place as you could hope to find in the whole world. It is also striking that the shootings are so random that there does not seem to be any police manhunt or newspaper outrage; Michio is actually arrested for walking in the wrong neighborhood late at night and only tied to the shootings after the police find the pistol still in his pocket.

All in all, a fascinating movie, but still frustrating.

* The real-life case originally tried the young man as a juvenile, a decision which was later overturned, then went through many appeals, but ultimately resulted in his execution almost thirty years later.

Murdering taxi drivers seemed like his only effective plan for making money; the fact that his only outfit is a suit makes this plausible. When he used the same strategy a second time, it seemed like his first planned action: a sort of progress, however horrific….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: If You Were Young: Rage / Kimi ga wakamono nara (1970) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Wet Sand in August / Hachigatsu no nureta suna (1971) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Attack at Noon / Attack on the Sun / Hakuchu no shugeki (1970) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Preparation for the Festival / Matsuri no junbi (1975) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: The Incident / Jiken (1978) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Bullet Train / Shinkansen daibakuha (1975) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Man Who Stole the Sun / Taiyo wo nusunda otoko (1979) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Third / Third Base / Sado (1978) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: The Strangling / Kosatsu (1979) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Beast Must Die / Beast to Die / Yaju shisubeshi (1980) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Village of Doom / Ushimitsu no mura (1983) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Rape and Death of a Housewife / Fatal Case of Assault / Hitozuma shudan boko chishi jiken (1978) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Revolver (1988) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Angel Dust / Enjeru dasuto (1994) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Bullet Ballet (1998) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Monday / Mandei (2000) | Japanonfilm

Pingback: Cold Fish / Tsumetai nettaigyo (2010) | Japanonfilm